1. Every Advantage Is Eroded

The pursuit of a sustainable advantage has long been the focus of strategy. But advantages last only until competitors have duplicated or out- maneuvered them. As will be seen in the discussions of Part I, protecting advantages has become increasingly difficult. Once the advantage is copied or overcome, it is no longer an advantage. It is now a cost of doing business. Ultimately the innovator will only be able to exploit its advantage for a limited period of time before its competitors launch a counterattack. With the launch of this counterattack, the original advantage begins to erode (see Figure 1-1), and a new initiative is needed.

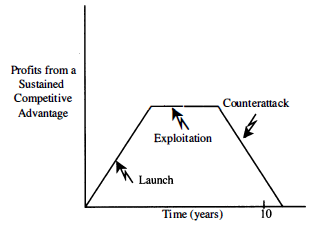

FIGURE I-1

EVERY ADVANTAGE ERODES EVENTUALLY

As shown in Figure 1-1, the cycles for launching and exploiting initiatives (new product introductions, for example) offer only a limited window of opportunity during which the firm can earn profits. Eventually, at the end of the cycle, the advantage is eroded by a counterattack. The competitive advantage of the firm is then lost. In the past, competitive advantage has always eroded, but it used to be over longer product life and product development cycles. Traditional strategic thinking has been to find ways to extend the plateau in Figure 1-1. Companies like IBM, GM, and Caterpillar all developed entry barriers and power over buyers and suppliers that extended for decades. But, as described in Part I, these cycles have compressed, and maintaining a sustainable advantage has become increasingly difficult. Obviously, advantages in cost and quality or timing and know-how are eroded by the actions of competitors. But even such seemingly unbeatable advantages as geographic or market entry barriers and deep pockets are proving to be little match for aggressive and innovative competitors, as examined in Chapters 3 and 4 of Part I.

2. Sustaining Advantage Can Be a Deadly Distraction

Of course, if companies can extend these plateaus of sustainable advantage, they can reap profits. So what is the harm of trying to sustain an advantage for as long as possible? In an environment in which advantages are rapidly eroded, sustaining advantages can be a distraction from developing new ones. It is like shoveling sand against the tide rather than moving on to higher ground.

Trying to sustain an existing advantage is a harvest strategy rather than a growth strategy. It is designed to milk what assets you have now rather than to seek new assets to build on. Even in high-growth markets old advantages based on old assets may not be the ones that will be the source of future success. A strategy of sustaining the advantage created by your existing assets creates a danger of complacency and gives competitors time to catch up and become strong.

The declining power of brands, described above, may be a result of firms seeking to sustain their static competitive strategies. Companies have rested upon the sustainable advantage of brand equity rather than building new advantages. Gillette’s success at rebuilding its brand through the launch of the Sensor razor and Lever Brothers’ success with Lever 2000 soap show the power of brands if they are coupled with a dynamic competitive strategy.

Both companies were able to shake up the status quo of their industries. Gillette introduced a technologically superior, upscale razor in a market dominated by disposables. Lever combined moisturizing, deodorizing, and antibacterial qualities into one bar of soap, crossing over the traditional divisions among products in the industry. “This proves people want new brands, especially in a category like soap that’s saturated with old ideas,” commented Al Ries, chairman of the marketing firm Trout & Ries, on the launch of Lever 2000.19

Gillette, in particular, didn’t stand still after Sensor’s success, but introduced a radically redesigned Sensor for women and a new line of personal care products. The company’s relentless pursuit of new advantages left some observers bewildered. As the Economist commented in describing Gillette’s launch of “a better version” of the Sensor razor in Europe: “Analysts were mystified. The original Sensor is still selling well.”20 But Gillette has learned that rather than milk its current advantage for all it is worth, it must move on to its next advantage—or its competitors will.

Attempting to sustain an old advantage can eat up resources that should be used to generate the next move, thereby inviting attack by savvy competitors who realize that complacency has set in. Sustaining advantage is effectively a defensive strategy designed to protect what a firm has. In hypercompetition the better defense is often a strong offense.

Digital Equipment Corporation tried to sustain its advantage in minicomputers. It had posted a 31 percent average growth rate from 1977 to 1982 by focusing on the minicomputer. But the company clung so tenaciously to its advantage in minicomputer technology that it failed to develop a strong position in the emerging markets for microcomputers and personal computers.

As CEO Kenneth Olsen commented in a 1984 Business Week article, “We had six PCs in-house that we could have launched in the late ’70s. But we were selling so many [Vax minicomputers], it would have been immoral to chase a new market.’21 By 1992 Business Week notes, DEC had “ousted” Olsen and took $3.1 billion in charges over two years, to cut 18,000 jobs and close 165 facilities.22 Its pursuit of a sustainable advantage may have left it without the series of temporary advantages it needed to thrive in a hypercompetitive market where competitors just destroyed Digital’s advantage by outmaneuvering it.

Even such a successful competitor as Matsushita, which has been cited as a paradigm of successful management and competition, stumbled in hypercompetitive markets by not moving on to new advantages. The Wall Street Journal reported consolidated pretax earnings in 1992 tumbled by 39 percent. The Journal notes, “To ensure its long-term health, what Matsushita really needs to do is start looking for new areas of growth. Yet the company traditionally has been a laggard at developing pathfinding new products with world-wide appeal. … Matsushita also hasn’t been aggressive in developing an emerging new wave of products combining consumer electronics with computers and telecommunications, even though it produces most of the components.”23 Even for the largest and most successful of competitors, past advantages are no guarantee of future success.

3. The Goal Is Disruption, Not Sustaining Advantage

If companies are not seeking a sustainable competitive advantage, what is the goal of strategy in hypercompetitive environments? The primary goal of this new approach to strategy is disruption of the status quo, to seize the initiative through creating a series of temporary advantages.

If a company’s goal is to sustain advantage, it tries to create an equilib, rium in its industry at a point at which it has an advantage. Part I will demonstrate the futility of this approach. In hypercompetition, however, the company’s goal is to disrupt the industry to create new advantages and erode those of competitors. By creating a series of these disruptions, com, panies can keep one step ahead of their competitors, moving from one temporary advantage to the next.

A survey of the fifty oldest U.S. companies found that they have persisted not by exploiting a single advantage but “by ceaselessly altering and renewing their technologies and products and sometimes, too, their capital structures.’ These oldest companies have done more than survive; they outperformed the Standard & Poor 500 in 1991. To take just one example, the oldest U.S. public company, the Dexter Corporation began as a cloth mill in 1767, moved to turning rope into wrapping paper, and then moved to producing teabags and meat casings, as well as automotive gaskets. I t is now moving into new areas such as aerospace and medical fabrics.24

Strategies such as “stick to your knitting” and “build off your core com, petence” may maximize short,run performance and profitability by using the same assets over and over again. But these approaches do not provide the guidance for true long-run survival. While they may generate shortterm profits, these strategies ultimately leave companies with a tired, outdated asset base that is not adapting to the future. Instead a new approach is needed.

4. Seizing the Initiative with a Series of Small Steps

As competitive cycles have shortened, the need to rapidly develop new advantages has increased. It has become more important for companies to focus on generating their next advantages even before their current advantages erode. The traditional goal of strategists has been to find a grand and long-term strategy that sustains itself for years or even decades. Today this is becoming rare, if not impossible. The grand, long-term strategy is often outmaneuvered, so it rarely wins. It often takes too long to create the assets needed to pull off this grand strategy. By the time a firm has the assets in place, they are obsolete or the circumstances have changed so much that new and better alternative strategies have emerged. The days where it is possible to do five- and ten-year strategic plans are coming to an end as changes hasten. It is the rare industry where a firm can predict how technology, customers, regulation, competition will look in ten years. Even five years is difficult. In 1988, who knew that, by 1993

- Russia would be a new capitalist market?

- One of the leaders of the Japanese juggernaut, Matsushita, would stumble?

- Chrysler and Ford would reseize the initiative in the car industry?

- Cold fusion may instead be for real?

Just to name a few of the surprises over the last five years.

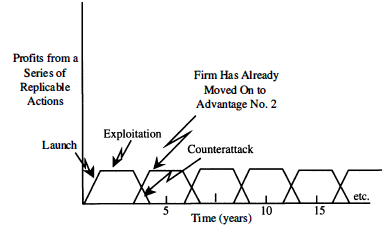

Instead of long-range plans and enduring competitive advantages, a succession of small, often easily duplicated strategic attacks are more typically used in rapidly changing hypercompetitive environments. By stringing together a series of these short-term advantages, the firm can effectively create a long-term sustainable advantage in the marketplace (see Figure 1-2).

Both Microsoft and American Airlines have used a series of initiatives to keep bringing their customers back into the fold. Although many of these innovations have been copied by the competition, the steady stream has helped these companies succeed. If Microsoft had rested on its laurels with MS-DOS in the way that Digital clung to the minicomputer, it would have been laying off employees rather than continuing to expand.

FIGURE I-2

A SERIES OF SHORT-LIVED ACTIONS ADD UP TO A

SUSTAINED ADVANTAGE

American’s advantages were even more easily copied. At each stage in the development of American’s strategy, competitors moved in and duplicated American’s advantage. But by the time the competitors arrived on the scene, American had already built a new advantage through its next innovation. So American, even with its reservation system, has been successful through a series of nonsustainable or imitated actions. Its advantage resulted because it did them first and frequently.

These moves were not a random series of actions. Each created an advantage or disrupted the marketplace by destroying an advantage of its competitors. American seized the initiative by finding ways to serve its customers better than other carriers. It did so by identifying the business traveler as a customer for the first time, searching for new opportunities within its current markets, and shifting the rules of competition from competition on price and service to competition on perks. Each of these actions by American forced competitors onto the defensive because they had to rise to the challenge or be left behind.

Source: D’aveni Richard A. (1994), Hypercompetition, Free Press.