We begin with national labor unions. As we have noted in earlier chapters, ecological analysis of unions has special sociological interest because unions have combined elements of social movement and bureaucracy. The fact that unions have often had the character of social movements allows a range of sociological theory to be used in analyzing their life histories in addition to the theories we have emphasized.

We set the stage for our treatment of the life chances of unions by restating the implications of Michels’ famous analysis of oligarchical tendencies in labor unions. We suggest that his views can be recast with profit into the framework of organizational ecology. In particular, we suggest that Michels’ theory has implications for density dependence in the disbanding rates of labor unions and other kinds of social-movement organizations.

Many sociological analyses of the labor movement emphasize organiza- tional aspects of the history of the labor movement. Much of this literature concentrates on the observation that social movements increase their chances of wide-scale coordinated action by developing formal organizations with differentiated administrative structures and procedures for maintaining flows of resources and taking collective action (Tilly 1978). Although building a permanent organization facilitates collective action, it also imposes constraints on action. The classic statement on the consequences of organization-building for social movements is Michels’ thesis of the iron law of oligarchy (1915/1949, p. 70): “Organization implies the tendency to oligarchy. In every organization, whether it be a political party, a professional union, or any other association of the kind, the aristocratic tendency manifests itself very clearly. The mechanism of the organization, while conferring a solidity of structure, induces serious change in the organized mass, completely inverting the position of the leaders and the led.”

Subsequent research has shown that Michels’ claim of the inevitability of oligarchy in trade unions is not quite an iron law. For example, Lipset, Trow, and Coleman (1956) showed that the International Typographic Union has maintained a competitive two-party system. Yet the ITU stands alone among American unions in having a competitive political structure. Other American unions have exhibited contested politics at various times as insurgent groups challenged leadership. The political turbulence occasioned by such insurgencies gives testimony to the strength of oligopolistic tendencies in the American labor union movement over most of its history.

We concentrate on a less well remembered aspect of Michels’ theory (1915/1949, pp. 338-340) as it pertains to unions: “From a means, organi- zation becomes an end . . . The sole preoccupation is to avoid anything that may clog the machinery. Thus the hatred of the party is directed, not in the first place against the opponents of its own view of the world order, but against the dreaded rivals in the political field, against those who are competing for the same end—power . . . Evidently among the trade unions of diverse political coloring, whose primary aim is to gain the greatest possible number of new members, the note of competition will be emphasized more.”

This section follows the Michelsian tradition by analyzing the conse-quences of competition among unions for their life chances. In doing so, it examines unions both as social movements and as organizations. It takes seriously the idea from labor history and social movement research that the life chances of unions have been affected by environmental events that altered the resources available to the union movement and by competition between unions and management. It also uses Michels’ notion that competition among unions for members and political power also affected the life chances of unions profoundly. In particular, this section asks whether competition among unions has played a role in stalling the growth of the union movement. It does so by examining the effects of competition among unions on the rates at which unions disbanded.

We recast Michels’ views about competition among rival social-movement organizations in ecological terms. However, we think that Michels considered only one side of the process. In our view, rivalry does affect the fates of social- movement organizations when density is high and the field is crowded. Yet this is not the only way in which density affects the life chances of these and other kinds of organizations. We suggest that there are two opposing processes by which density affects life chances: first, growth in numbers in organizational populations provides legitimacy and political power; second, increasing density exhausts limited supplies of resources for building and maintaining organizations and thereby increases both direct and diffuse competition. Our theory holds that the first process dominates at low densities and the second (Michelsian) process dominates at high densities.

1. The Etiology of Disbandings: Views from Labor History

We begin by reviewing common arguments in labor history about the causes of disbandings. This review provides some institutional context for our ecological analysis, giving numerous concrete examples of the phenomena of interest. It also has implications for the design of our research. We are not interested primarily in evaluating whether these historical claims stand up in the face of systematic comparative analysis. However, we do want to control for the effects of relevant causal factors other than those identified by ecological theory. So this discussion identifies a set of covariates to be used as “control variables” in our analysis and also suggests some potential alternative explanations.

Labor historians sometimes explain union disbandings by alluding to particular catastrophes. These include misjudged or mistimed actions by the union, actions of those in other organizations such as the state or federations of employers, and sharp, unexpected swings in the economy. The most vivid examples of catastrophes involving the actions of unions and their opponents are large, often violent, strikes in which a union is crushed. When the famous Pullman strike occurred in 1894, the radical American Railway Union had grown to roughly 140,000 members since its founding the year before. The union was destroyed by federal troops enforcing court injunctions. Union leaders were jailed and eventually convicted, and the American Railway Union disbanded. In a recent case, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization, founded in 1970, disbanded in 1982 after striking controllers were fired and replaced at the order of President Reagan.

Some catastrophes involved concerted action by employers and by asso- ciations of employers during periods in which unions were weak or public opinion seemed to have turned against them. Taft (1964, pp. 212-229, 361— 371) describes widespread employer offensives between 1903 and 1908 (led by the Citizens Industrial Association, the American Anti-Boycott Associ- ation, and the National Council of Industrial Defense) and in the period 1919- 1929 (with the American Plan of Employment, an open shop campaign mounted by a national conference of state manufacturing associations). Unions such as the Oil and Gas Well Workers (1889-1905) and the Timber Workers (1917-23) have been depicted as victims of the success of these employer offensives (Fink 1977).

Actions by agencies of government also have proved catastrophic to unions at times. An interesting case concerns the Foremen’s Association of America, founded in 1941. By 1947 this union had organized 28,000 supervisory employees, mainly in the auto industry. After passage of the Taft-Hartley bill that year, which held that existing labor laws no longer applied to supervisory employees, numerous firms declared their contracts with the Foremen’s Association to be void. The union disbanded shortly thereafter. On the other hand, some governmental actions apparently lowered the risk of disbandings. It is widely agreed that the Wagner Act, which institutionalized collective bargaining and legitimized business unions, had such a stabilizing effect.

Many disbandings have been attributed to economic upheavals. During financial panics, such as the panics of 1837, 1853, and 1873, many businesses failed and unemployment surged. Apparently, union members deserted unions in the interest of finding or keeping scarce jobs during these crises.

Labor leaders and scholars have emphasized the role of immigration in disrupting the union movement. Although the pool of immigrant labor provided many labor leaders and large numbers of class-conscious workers, immigration reduced the power of unions by providing a source of cheap (and nonunionized) labor and by supplying a ready pool of strikebreakers (Bonacich 1976). Foner (1975, p. 17) asserts that “all too frequently newly-arrived immigrants of every nationality made their first entrance into American industry as strikebreakers … To list the unions weakened or destroyed or the strikes broken in the ’eighties by industry’s policy of introducing immigrant labor or strikebreakers would require many pages.”

Historians have often argued that such catastrophes destroyed unions that were already vulnerable for other reasons, such as youth, declining membership, and inability to adjust to technical change. The following are the most widely cited causes of long-term decline of the kind that would make unions susceptible to disbanding in the face of environmental catastrophe.

Some unions never developed effective routines for organizing members, collecting dues, and engaging in collective bargaining. Such failure to develop procedures for sustaining an organization made some unions highly vulnerable to internal and external shocks. At least three unions disbanded in rancorous internal conflict after officers embezzled their treasuries: the American Longshoremen’s Union (1897-8), the Journeymen Tailors National Trades Union (1865-76), and the Switchmen’s Mutual Aid Association (1886-94).

Inability to adapt to technical change or to control it is often cited as a cause for the downfall of unions that organized a set of named crafts or jobs. As employers adopted new technologies, the distinctions among jobs changed quickly and crafts became obsolete. The titles of some disbanded labor unions from the nineteenth and early twentieth century illustrate the problem: the Horse Collar Makers’ National Union (1888-93), the Window Glass Snappers’ Union (1902-8), the Associated Brotherhood of Iron and Steel Heaters, Rollers, and Roughers (1872—6), the Brotherhood of Tanners and Furriers (1892-5), the Gold Beaters’ Protective Union (1897— 1907), and the Union of Shipwrights, Joiners and Caulkers (1902-11).

Even old, successful unions of skilled workers, such as the International Typographic Union (1850-1985), managed only to slow the tide of technical changes that eventually made their crafts obsolete (Wallace and Kalle- berg 1982). More typical is the case of the Knights of Saint Crispin (1867— 78), the first really large union in the United States. The Knights organized skilled workers in the shoe industry in order to forestall competition from semi-skilled workers (“green hands”) on machines. The tactic used to forestall technical change was to prohibit members from offering instruction to green hands in any of the techniques of shoe making. Since machine workers did not need to learn craft skills, the tactic failed. Although the Knights grew very rapidly (its peak membership was estimated to be 50,000 to 80,000), it also declined very quickly when it became apparent that the strategy could not slow the mechanization of shoe making (Lesco- hier 1910). The combination of organizational inertia and rapid technical change apparently caused the downfall of many craft unions.

Labor historians have also stressed the role of direct competition, sometimes called interunion rivalry, as a cause of decline and eventual disbanding or merger (Galenson 1940, 1960). It was common for two or more unions to attempt to organize the same set of workers. Such rivalry was sometimes due to expansion of unions that had begun in different sections of the country; for example, the Western Federation of Miners (1893— 1982) competed with the (mainly Eastern) United Mine Workers (1890— 1985) before merging with the United Steelworkers. Sometimes the rivalry reflected disagreements over politics or tactics, as in the case of the conservative Journeymen Tailors’ Union (1883-1914) and the mainly socialist Tailors’ National Progressive Union (1885-9). At other times a national federation created an affiliated union to compete with an independent union. For example, the American Federation of Labor created the American Federation of Musicians (1896-1985) to compete with the National League of Musicians (1886-1904) after the NLM repeatedly refused to affiliate with the AFL.

Another kind of head-to-head competition pitted craft unions against industrial unions and against unions that organized multiple crafts, the so- called compound craft unions (Ulman 1955). For example, as mentioned in Chapter 7, the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners (1881-1985) claimed jurisdiction over all wood workers. The UBC fought jurisdictional battles with and raided the membership of unions such as the International Union of Timber Workers (1917-23), the Furniture Makers’ Union (1873— 95), the Laborers International Union (1903-85), the Association of Sheet Metal Workers (1888-1985), the Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees and Moving Machine Operators (1893-1985), the Woodcarvers’ Association (1883-1945), and the International Woodworkers of America (1936— 85). Interestingly, even though the UBC was a major element in the AFL, it took most of these actions over the strong objections of the federation (see Christie 1956).

Much rival unionism involved competition between national federations promoting different forms of unionization. The most important example was the competition of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, a federation of industrial unions, with the American Federation of Labor, a federation of craft unions. After the founding of the CIO within the AFL in 1936 and its expulsion in 1938, the CIO was instrumental in founding industrial unions to compete with AFL unions (Galenson 1940, 1960). For example, the CIO created the United Paperworkers’ International Union (1944-57) to compete with the AFL-affiliated Brotherhood of Paper Makers (1902— 57) and the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union (1937-79) to compete with the Retail Clerks’ International Association (1890-1979). Sometimes jurisdictional struggles and raids on memberships of rival unions were resolved by a merger of the competing parties. However, in many cases one of the competitors was destroyed and its members absorbed individually.

2. Population Ecology Analysis

Historical accounts of disbandings are useful for identifying factors that appear to affect union mortality. But they are not appropriate for assessing competing arguments about the causal structure. Meaningful causal analysis requires study of unions that faced comparable catastrophes and did not disband. That is, restricting analysis to unions that disbanded distorts causal inferences about the causes of disbanding. This is a clear instance of sample selection bias (Heckman 1979; Berk 1983). We depart from the labor history tradition by analyzing the entire population of national unions over the full 150-year historical period. This strategy avoids problems of selectivity bias and permits consideration of the joint operation of the various hypothesized causes of disbanding.

Our first objective is to learn whether density affected disbanding rates in the predicted non-monotonic manner. Figure 11.1 shows variation in the yearly count of disbandings over the period. As in the case of union foundings (Figure 9.1), the peak occurs in the middle of the series. Given the strong liability of newness, this is not surprising. Periods of peak foundings will tend to be followed by periods of high rates of disbandings as a result of the presence of many youthful organizations. As we insisted in the previous chapter, the effect of aging must be taken into account in assessing the effects of density and other factors.

Effects of aging are included in all models estimated in this section. Given the findings of the previous chapter, we use a Weibull model of age dependence. More precisely, we use a step-function approximation to the Weibull model. This approximation uses the logarithm of age at the beginning of each year as a covariate in the log-linear model. We break each union’s entire history into Pt periods, where Pi, is the completed age of the union in years, and we update the union’s age (and all time-varying covariates) at the beginning of each year. In other words, the history of a union that existed for 15 years is represented by 15 spells. Let p denote the union’s age at the beginning of each of these spells. Then we approximate the Weibull model of age dependence with

![]()

Figure 11.1 Labor union disbandings by year DISBANDINGS

To a reasonable approximation, a = p – 1, where p is the parameter of the Weibull model defined in Chapter 8.

Properties of individual unions considered include the type of starting event. We distinguish unions that began with foundings and those that began with secessions from those that began with mergers (the excluded category). In addition, we construct simple measures of each union’s form. These are dummy variables that distinguish: (1) craft unions (those that organized on the basis of occupation or craft) from industrial unions, (2)unions whose target membership consisted solely of unskilled and semiskilled workers from those that organized at least some skilled workers, and (3) independent unions from those that belonged to any of the national federations such as the AFL and CIO. Because these characteristics can and do change over the lifetime of a union, we treat them as time-varying covariates. Their values were updated at the beginning of each year for each union. In addition to these characteristics, we also explore the effects of each union’s initial membership size.

We also include the effects of conditions in the economic and political environments. Our records on foundings, mergers, and disbandings of unions begin in 1836, more than 20 years before the first census of business and manufacturing. Even when such censuses began in 1859, coverage of firms and establishments was spotty and accuracy of information was doubtful. Still, as we argued earlier, it is crucial to include information on disbanding rates for the full period. Our insistence on using the full 1836- 1985 period places strong constraints on choice of measures of environmental conditions. The set of measures used is listed below. Unless noted otherwise, the source is the U.S. Bureau of the Census, especially The Historical Statistics on the United States: Colonial Times to 1970.

Economic catastrophes are measured with an index that identifies de- pression years, taken mainly from Thorp and Mitchell (1926). This measure records eight depressions during the 1836-1899 period and four between 1900 and 1985. Other measures of swings in general economic conditions include the number of business failures (1857-1984), the unemployment rate (1890- 1984), gross national product per capita (1889-1984), and the real wage rate of common laborers (1836-1974), taken from David and Solar (1977).

Some analyses of labor union history have stressed the importance of the rise of a national market for the success of national unions. It is difficult to find indicators of the nationalization of economic activity over this long period. We have tried to address these issues by considering the effects of the extension of transportation services essential to the rise of national markets. The relevant transportation indicators change from period to period—first canals, then railroads, then interstate trucking and airlines. Because the crucial period of the expansion of the union movement occurred during the railroad era, we focused on the expansion of this form of transportation, using a measure of miles of railroad track constructed per year. Unfortunately the available series, which begins before 1836, has a gap between 1880 and 1893 and ends in 1925. So use of this indicator leads to a major loss of observations. This does not appear to be a serious problem, however, because other indicators such as GNP and the period effects are likely to pick up the effects of major changes in the speed and cost of transportation and communication.

Technical change and intensification of production are measured on the basis of capital investment in plant and machinery (1863-1971) and patents issued for inventions (1836-1984). We also use a measure of the total yearly flow of immigrants (1836-1984) as well as year-to-year changes in levels of immigration in some analyses. Our data do not contain information about the timing of strikes for a particular union. Instead, we used a measure of aggregate strike activity: number of strikes in a year (1881— 1980).

We also explore the effects of historical periods. Claims that the political and economic structures facing unions changed qualitatively at certain points in history are addressed by using “period effects.” That is, we specified models that allow the rate to shift at certain specified dates. We have tried several sets of periods. Most do not improve the fit of the models significantly (at the .10 level) over models that contain the other covariates of interest (including density, age, and type of founding). Nonetheless, we include a set of period effects in all models we estimated in order to ensure that the estimated effects of density do not reflect unobserved effects of secular changes in the society or of changes in the legal and political standing of unions. The analysis reported below breaks the 150-year history into the same five periods used in previous chapters.

We also used period effects to deal with the claim that coordinated nationwide offensives by employers raised disbanding rates. Although it is difficult to find agreement on the precise dates of these offensives, it seems clear that the peak periods were 1903-1908, the period of a national “open shop” drive, and 1919-1929, the period of the so-called “American Plan of Employment” campaign led by the National Association of Manufacturers (see especially Taft 1964, pp. 212-229, 361-371). We constructed a dummy variable that distinguished years of these employer offensives from other years. Finally, we also used period effects to deal with the possibility that wartime conditions affected the life chances of unions. We used periods that distinguished years during the Civil War, the two world wars, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War as well as periods that distinguished only the two world wars (during which unions were given a relatively protected status under wartime production controls).

As in analysis of foundings, density is measured as the number of unions in existence at the beginning of each calender year. The count of recent disbandings is the number of disbandings recorded in the previous calender year.

3. Estimation

In order to allow values of the covariates to vary over the lifetimes of unions, we broke each union’s history into a sequence of yearly spells. The histories of the 621 unions (which number excludes the 12 Trade Union Unity League unions) provide 17,896 spells. Only 191 of them end with a disbanding; the rest are censored on the right. Age and the values of all covariates are updated at the beginning of each year for each union. However, all covariates are constant within years.

In some analyses, we also added a gamma-distributed disturbance term to the Weibull model in order to represent the effects of unobservable heterogeneity. That is, we estimated generalized gamma models. Surprisingly, we found that this more complicated model did not improve the fit significantly at even the .10 level over the Weibull model. Apparently the set of covariates in our models does an adequate job of picking up the main heterogeneity in the population. Therefore, we rely on the Weibull model.67

4. Results

We begin analysis with a baseline model that includes the effects of aging, type of starting event, waves of disbandings, and several environmental factors. Then we add density dependence to the baseline. Next we add other characteristics of the individual union as covariates. Finally, we explore the consequences of altering the representation of environmental processes.

The estimates of the baseline model appear in the first column of Table 11.1. The effect of aging is strong, as would be expected given the findings of the previous chapter. The estimated scale parameter indicates that the rate of disbanding drops sharply with aging. Even when these various time-varying covariates are included in the model, we continue to find a strong liability of newness.

The first column of Table 11.1 also reports the effects of a core set of covariates. This set includes only those covariates that are available for the whole period (1836-1985), meaning that the estimates of these models use the entire set of observations. In addition, only estimates of those covariates appearing to have systematic effects on the rate are included in the baseline model. These are type of starting event, indicated by the pair of dummy variables that distinguish foundings and secessions from mergers, a dummy variable that equals unity for depression years, and the four period effects.

As we saw with somewhat different models in the previous chapter, type of starting event has a powerful effect on disbanding rates. Unions whose starting event was a founding had disbanding rates roughly eight times larger than those beginning with a merger, while unions whose starting event was a secession had rates about four times higher than the merged unions. Disbanding rates rose during economic depressions, as labor historians have noted. Adjusting for age and other covariates, disbanding rates were 37 percent higher during depression years.

It is worth considering the estimated effects of periods in some detail because they have a different meaning from that in the previous chapter. In Chapter 10, the periods were defined as the period in which a union started; so the effect of a period was the effect of having begun in that period. Here period effects are defined for each year of a union’s existence. That is, each union’s disbanding rate is allowed to change across the periods that its existence spans. So in this chapter period effects tell the effect of a period on all unions in existence in a period, regardless of their period of beginning.

Estimates of the period effects tell that the rate did not change appreciably from the first to the second period, beginning in 1887. Net of other included factors, the disbanding rate seems to have been constant over the first century of the national union movement. But the onset of the New Deal, Period 3, had a powerful effect, reducing the rate to about half of its previous level. Extensive legal protection for union organizing seems not only to have stimulated membership growth of unions, as many have noted, but also to have depressed the disbanding rate of unions.

Somewhat surprisingly in view of the negative implications of the Taft- Hartley Act for unions, the period beginning in 1947 had an even lower disbanding rate than the New Deal period. However, the estimated negative effect of the fourth period does not differ significantly from zero. So a cautious conclusion is that the rate during the brief fourth period did not differ from the New Deal rate. Finally, the rate seems to have jumped during the final period, whose start marks the merger of the two major federations of unions and the beginning of long-term decline in the share of the work force represented by unions. However, the rate in the fifth period does not differ significantly from that of earlier periods.

The number of disbandings in the previous year also has a positive effect, as predicted. However, it does not differ significantly from zero in this and most other models we estimated. There is no strong evidence here that waves of disbandings affected the subsequent rate, when other relevant variables are controlled.

Next we turn to density dependence. The results of many different analyses reveal that the effect of density on the disbanding rate is indeed non- monotonic, as predicted. For instance, a comparison of columns 1 and 2 in Table 11.1. shows that adding the log-quadratic effect of density improves the fit significantly. More important, the estimated effect of density in the second column has the signs predicted in (11.2): the first-order effect, β1, is negative and the second-order effect, β2, is positive.

It is worth emphasizing that estimates of the effects of density are stable

and significant even in the presence of strong effects of aging, periods, environmental conditions, and founding conditions. Moreover, as we show later in this section, the estimated effects of density are quite robust with respect to specification of the environmental determinants of disbanding rates. The third column of Table 11.1 adds three covariates describing a union’s organizational form: (1) craft versus industrial form; (2) organizing only less skilled workers versus organizing some skilled workers; and (3) independence versus membership in a national federation. Since measures of the first two distinctions are unavailable for some unions, the number of spells used to estimate the model is smaller than in the first two columns. According to the table, none of the three measures of form affects the disbanding rate strongly or significantly.

Finally, the fourth column adds the log-size of initial membership to the model in the second column. Because information on size is unavailable for some unions, this addition too causes some loss of observations. As in the analysis in the previous chapter, which did not incorporate time-varying covariates, initial size has a significant positive effect on the disbanding rate.

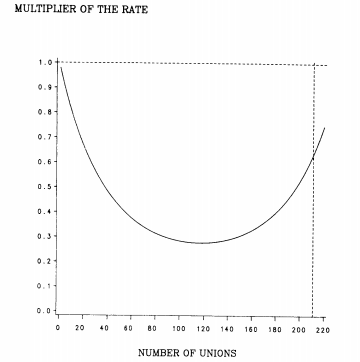

The estimated parameters in columns 2-4 in Table 11.1 imply that the effect of density changes sign within the historical range of density [0,211]. The point of inflection implied by these estimates and the relationship in (4.3) is N ≈ 122. Figure 11.2 plots the estimated effect of density on the disbanding rate, using the estimates from the second column of Table 11.1. The effect of density, the multiplier of the rate, reaches a minimum of 0.26 at N = 122. This means that the implied rate when there were 122 unions in the population was only a quarter as large as at a density of zero (for any combination of age and covariates). When density equals its historical maximum (N = 211), the multiplier equals 0.59. In other words, as the number of unions rose from 122 to 211, the disbanding rate more than doubled in the sense that the multiplier rises from 0.26 to 0.59. In fact, the estimated multiplier at the observed maximum of density is the same as when N ≈ 20. The process has come almost full circle. This pattern provides strong support for the theory developed in Chapter 6.

Figure 11.2 Effect of density on disbanding rate of unions (estimates from model 2 in Table 11.1)

We also explored the consequences of adding each of the environmental covariates discussed earlier. We added each covariate in turn to the model whose estimates appear in the fourth column of Table 11.1. That is, we added each covariate in turn to a model that contains the effects of age, type of starting event, independence, depression year, and the period effects. The results of a portion of this exercise appear in Table 11.2. This table reports estimates of the effects of the two density terms and each covariate, but not the effects of all the other variables in each model because they are quite stable from model to model and differ little from the estimates discussed above. Table 11.2 lists the environmental variables in order of decreasing coverage of the historical period (in terms of number of events excluded when the covariate is entered into the model). So the columns to the left side of the table contain estimates that used more of the historical information than those to the right.

The effects of most covariates are slight. Only three have estimated effects that differ significantly from zero at the .10 level: periods of employer offensives against unions, capital investment in plant and equipment, and gross national product per capita. The finding regarding capital investment suggests that the spread of mechanized factory production enhanced the life chances of labor unions. This finding agrees with the general thrust of Marx’s model of mobilization—concentration of workers in large enterprises eases the communication and interaction necessary for collective action. The negative effect of GNP can be given a similar interpretation.

The other significant effect is puzzling: it indicates that disbanding rates fell during periods of nationwide employer offensives. It is hard to believe that these offensives actually reduced the rate, unless the offensives somehow caused unions to take defensive actions that gave them a resistance to disbanding that they would otherwise not have possessed. More plausibly, other changes occurring during the first and third decades of this century may have lowered the disbanding rate. Nonetheless, this finding raises questions about the claim that employer offensives had powerful negative effects on the union movement (Griffin, Wallace, and Rubin 1986).

We find no evidence that disbanding rates were affected by wars, immi- gration flows, strike waves, or size of the labor force. Likewise, the variety of indicators of economic activity (the real wage rate of common laborers and the unemployment rate) fail to affect the rate significantly when union characteristics, density, the occurrence of economic depressions, and the differences among periods are taken into account. The same is true when levels of economic conditions are replaced by variables measuring year-to- year changes in these conditions.

Given the objectives of this chapter, the behavior of the estimated effect of density when the covariates are entered into the model is particularly important. The non-monotonic pattern of density dependence is quite robust. In all 12 models in Table 11.2, the first-order effect of density is negative and the second-order effect is positive, as predicted.

Although the qualitative pattern is stable, the point estimates differ among specifications. We think that there are two sources of such variation. The first source is sampling error due to the fact that the cases used in each analysis differ because of missing values on covariates. The second source is that the relevant range of variation in density differs from column to column as the years of coverage change (also because of missing values on covariates). Consider, for example, the results in the model that contains the effect of gross national product per capita. If the estimated effect of density is evaluated over the entire range of density, it implies that the disbanding rate declines sharply beginning at TV = 0 and rises only slightly at high density. But the relevant range of variation in density in this analysis does not include the region of low density. Since data on GNP are available beginning only in 1889 when the level of density was N — 79, the estimated effects of density should be evaluated only over the restricted range [79,211]. And over this range, the effect of density is indeed nonmonotonic.

In all but two cases, both the first-order and second-order effects of density differ significantly from zero. The exceptional cases are the models in columns 8 and 9, which include the effects of capital investment and counts of strikes. These indicators are missing in years in which the density of unions is far below the apparent carrying capacity. The estimated first-order effects and, to a lesser extent, the second-order effects are somewhat diminished relative to other models. However, it is clear that the necessity of dropping a large part of the historical record increases the standard errors of estimate. For this reason we do not think that these exceptions cast serious doubt on the pattern that holds with the alternative specifications. In our view, analysis of this set of possible covariates does not alter the conclusion reached above. Density, measured in terms of number of unions, affects the disbanding rate in the predicted way. These effects are large in substantive terms, and they differ significantly from zero in all but two models.

5. Competition between Populations

Finally, we explore the effects of competition between populations. We continue to distinguish craft unions, which organized a named set of occu- pations or jobs, and industrial unions. In preliminary analysis we found that the effects of age and the covariates were fairly similar for the two populations. Therefore, we have pooled them together and estimated models in which the effects of age, periods, and covariates are constrained to be the same for both craft and industrial unions. However, we have allowed the effects of density to differ for the two subpopulations. That is, we specify that the disbanding rate in each population depends on its own density (in log-quadratic form) and on the density of the other population as in equation (11.3), and that the parameters indexing these dependencies may differ between subpopulations. We also allow for a main effect of the difference between craft and industrial unions, using a dummy variable that equals one for industrial unions. Table 11.3 reports ML estimates of this model.

Consider first the effects of own density. For both craft and industrial subpopulations, own density has a negative first-order effect and a positive second-order effect, as predicted. However, the effects differ considerably between the subpopulations. The estimated effect of own density (Nc) for craft unions implies that the disbanding rate falls with increasing own density until NC = 77. This point of inflection falls roughly halfway between zero and the observed maximum of 156. At this level of craft density, the multiplier reaches its minimum level of 0.46. This means that legitimation processes associated with increasing density have cut the disbanding rate by slightly more than one- half when density equals 77. From that point on, growth in NC increases the disbanding rate. When NC reaches its observed maximum, the multiplier is close to unity (1.03), which means that the disbanding rate is essentially the same in a population of 156 craft unions as in a population with zero density. Thus, competition within the population of craft unions had eroded all of the disband- ing-reducing effects of legitimation when craft density reached its peak level.

Legitimation apparently has had a much stronger effect in the population of industrial unions. The estimates in Table 11.3 imply that the disbanding rate of industrial unions reaches its minimum at Nt = 50, just below its peak level of 52. So the disbanding rate of industrial unions falls with increasing density over almost the entire range. In fact, the rate has been driven close to zero at this point. Legitimation processes have clearly dominated processes of intra- population competition for industrial unions.

Next consider the effects of competition between subpopulations, as indicated by the cross-effects of density. Density of craft unions (NC) has a significant positive effect on the disbanding rate of industrial unions. But Ni has a negative and insignificant effect on the disbanding rate of craft unions. So again we find that competition processes in the world of national unions have been asymmetric. Craft unionism suppressed industrial unionism, but the reverse was not true.

The estimated effect of craft density on industrial disbandings is strong. When the number of industrial unions reached its peak in 1939, the number of craft unions was also large by historical standards. We have already noted that the negative effect of own density drives the industrial union disbanding rate close to zero under these conditions. But this effect is partly offset by a strong positive effect of craft union density. Still the effect of Af/ dominates, and the implied disbanding rate was only 20 percent as large as under zero density in each population. Yet these estimates also suggest that the density of craft unions strongly affected the life chances of industrial unions when industrial unions were not large in numbers. That is, in periods when industrial density was low, the high density of craft unions increased disbanding rates of industrial unions strongly. Still, the competitive effect was dwarfed by the strong legitimating effect of increasing density within the population of industrial unions.

We have emphasized the role of density in affecting disbanding rates as a way to explore the effects of diffuse competition and legitimation. As we had hypothesized, density of unions does affect disbanding rates strongly. It is clear that whatever else affected union disbanding rates—and economic and political conditions surely did—these rates were strongly affected by competition among unions. As Michels pointed out, the struggle was not simply one of conflict with employers or the state, as many discussions suggest. Rather, there has been intense competition within the population of unions over the 150-year period we studied. There has also been competition between craft and industrial unions. Yet density dependence also seems to reflect processes of legitimation. And we find strong evidence that increases in density lowered disbanding rates before density reached a high level.

Source: Hannan Michael T., Freeman John (1993), Organizational Ecology, Harvard University Press; Reprint edition.