To understand Menger’s explanation it is important to comprehend his story and its stages. Menger observes that there is a curious social phenomenon called ‘money’ and he wants to explain its emergence in order to understand its nature. He wants to find out how it could have emerged. Briefly, his task is to explicate how a no-medium-of-exchange world transforms into a world with a medium of exchange.

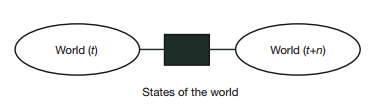

To explain the origin of money, Menger needs to find out the conditions under which a generally acceptable medium of exchange could emerge. That is, he needs to tell us about the state of the world at time t, World (t), and the processes that transforms World (t) into a state with a generally acceptable medium of exchange at time t + n, World (t + n). In Figure 3.1, the box in between the two states of the world represents the process (or mechanisms) that transforms World (t) to World (t + n). The description of World (t) and of its transformation into World (t + n) is needed to explain the emergence of money.

The problem here is the representation of the states of affairs in World (t) and World (t + n). It is relatively easy to represent World (t + n) for it is possible to observe the characteristics of a medium of exchange and how it is used. However, direct evidence about World (t) is limited. Menger states a couple of facts about different uses of money in history and in different cultures. He informs us that cattle, shells, etc. have been used as money, and that the concept of a medium of exchange is not limited with coins and papers issued by the state. He also mentions other general facts, such as the fact that different goods have differ- ent degrees of saleableness. In Menger’s explanation World (t) is described as a place where market-dependent individuals directly exchange goods at the market. Individuals of World (t) act according to their economic interests and are capable of improving their situation given the conditions of the market. The ‘economising actions of these individuals and their interaction’ is the main driving force in the transformation of World (t) into World (t + n).

Figure 3.1 States of the world.11

1. Objections

There are at least two important objections to Menger’s account.12 The first sug- gests that ‘money was introduced by a communal agreement or political decree or legislative action that is external to the exchange process’ (Iwai 1997: 1). The second argues that the origins of modern money should be traced back to gift ex- change, or more generally to transaction forms other than commercial exchange (see, for example, Clark 1993: 381–382). These accounts have different charac- terisations of World (t) and its transformation into World (t + n). The common de- nominator of these alternative accounts is their criticism of Menger’s description of the initial state within which money developed, that is, of World (t). It is argued that barter, the direct exchange of goods, is hardly found in earlier and primitive societies and the tendency to exchange goods, which is the main driving force in Menger’s explanation, is almost non-existent in those societies.

The design view may have various forms. Its simplest form focuses on coined money and justifiably argues that ‘money’ was designed. Obviously in this form, design view does not contradict Menger’s account of the origin of a generally acceptable medium of exchange.14 Those who argue that it does are confusing the different delineations of money used in these different views.15 Indeed, Menger would definitely agree that coined money is a matter of design:

by state recognition and state regulation, this social institution of money has been perfected and adjusted to the manifold and varying needs of an evolving commerce, just as customary rights have been perfected and adjusted by stat- ute law. Treated originally by weight, like other commodities, the precious metals have by degrees attained as coins a shape by which their intrinsically high saleableness has experienced a material increase.

(Menger 1892a: 255)

A more sophisticated form of the ‘design view’ argues that money neither de- veloped out of direct exchange, nor that it functioned as a medium of exchange in its early stages. Such an account can be found in Henry (2002). Henry ar- gues that in Egypt money first developed as a ‘unit of account’ (also see Ingham 1998a,b, 1999). Henry (2002: 5) informs us that ‘up to about 4400 BC. Egyptian populations lived in egalitarian, tribal arrangements.’ Then he explains how these non-exchange, non-propertied societies with collective production and collective consumption are transformed into a society with hierarchical (unequal) structures. The idea is that after the specialisation of some individuals on agricultural tech- niques, a classed structure emerges slowly and obligations that were internal to the tribe are transformed into obligations to other classes. ‘Under the new social organization, tribal obligations were converted into levies (or taxes, if one views this term broadly enough)’ (Henry 2002: 9).

At some early point in the Old Kingdom, the growing complexities of the new economic arrangements required the introduction of a unit of account in which taxes and their payment could be reckoned and the various accounts in the treasury could be kept separate and maintained. This unit was the deben.

(Henry 2002: 11)

In Henry’s story World (t) is a place where there is no market-dependent ex- change, but obligatory payments. Moreover, individuals are not equals in their transactions (e.g. they do not exchange goods voluntarily) as they are in Menger’s story. For this reason, Henry proposes this historical study as a case that contra- dicts Menger’s account, and supports Innes’s (1913) account that sees money as a product of obligations that existed in every society. Yet Henry’s account does not really contradict Menger’s account. Henry and Menger are explaining different things. Henry explains the emergence of money as a unit of account at a specific place and time. Menger, on the other hand, presents a general account of money as a medium of exchange. Thus, two differences can be identified: first, they explain different things; second, their explanations are at different levels of generality. As it stands, Henry’s design argument only holds for the emergence of money as a unit of account. It leaves the possibility that money as a medium of exchange developed spontaneously in that environment – that is, after the introduction of deben – with the development of market-dependent exchange. In any case, al- though we cannot establish that it contradicts Menger’s account in its conclusions, we have to acknowledge the fact that it presents a totally different perspective on the environment within which money as a medium of exchange developed. Thus, his evidence on Egypt arouses doubts about Menger’s description of World (t).

The inaccuracy of the traditional description (such as Smith’s, Menger’s, Jevons’s, etc. – as presented in Appendix I) of the stages of society prior to de- velopment of money has been emphasised by many anthropologists and histo- rians alike. Such criticism heavily builds on Polanyi’s (1944) influential book The Great Transformation.16 The main argument here is that primitive cultures do not have the institutions that modern cultures have and that the traditional view is wrong in imposing the modern definitions of similar institutions to those cultures. The fifth chapter of The Great Transformation is full of such examples. Polanyi argues, for example, that money is not necessarily an important institution in primitive cultures, for money serves different functions in such cultures that are of secondary importance to the functioning of those societies. He argues, contrary to the common view in economics that trade most probably developed as long- distance trade and not as internal trade, the exchange of goods was not in the form of barter but in the form of gift exchange. According to Polanyi, it is hard to find a state in history or in primitive cultures where individuals bartered goods and acted in line with their disposition to exchange goods selfishly ‘maximising’ their ‘utility’. Polanyi’s argument undermines the description of World (t) as presented by Menger.

Similarly, Bohannan and Dalton (1971) argue that ‘the familiar dichotomy of barter versus money transactions does not reveal the mode of transaction in goods changing hands’ in primitive cultures. In Polanyi’s terminology reciprocity, redistribution and market exchange are three different ways in which goods may change hands. Goods changing hands by reciprocal gift exchanges or by redis- tribution of the goods that were collected at a centre is essentially different from market exchange. Thus, in considering the evolution of money the traditional view (e.g. Menger’s) makes the mistake of ignoring these institutional arrangements by assuming the existence of barter.

Departing from similar arguments, some anthropologists argue that money evolved out of the gift system, which can be considered as a type of obligation.17 In this view money was not intentionally brought about; rather, it developed out of social obligations, that is, gift exchange. For example, Clark argues:

Menger omits the fact that money, as a social institution, existed thousands of years before the rise of the market economies. Just as the exchange of commodities has its origins in the ceremony of the gift, where the motivation is the exact opposite of that which we assume today, the origins of money are not connected in most instances to trade goods, but to a change in function of an object usually of ceremonial value.

(Clark 1993: 381–382)

Clark argues that different forms of money existed prior to the emergence of a generally acceptable medium of exchange and that Menger should have taken this into account in his explanation of origin of a medium of exchange. The seri- ous challenge here is that Clark argues that Menger does not get the facts right about the state of the world, World (t), within which a medium of exchange was brought about, and that Menger’s depiction of the earlier stages of the society ignores the most relevant institutions (e.g. prior forms of money). The objection is that explanation of the origin of a generally accepted medium of exchange or origin of modern all-in-one money cannot be independent from the prior forms of money (i.e. limited purpose money). It is, therefore, not possible to argue that Menger explains the genesis of money in a truly historical sense. If the description of the initial stages, that is, World (t), is not accurate, one is tempted to argue that Menger’s explanation is wrong and for that reason it is valueless. Is it possible that Menger’s exposition is still valid although its description of the initial stage, World (t), does not correspond to any stage of any society in history?

To answer this question we have to see the differences between the objections and Menger’s account. The main difference is that Menger’s account is general and that of the objections are not. The objections are pointing to some particular facts about the origin of money and their exposition is specific to certain locations and times. Menger’s account, on the other hand, is pointing out some general mechanisms that may have been working in particular histories of the emergence of a medium of exchange.18 In Menger’s terminology, objections provide a his- torical understanding, and Menger provides a theoretical understanding. The dif- ference between historical and theoretical understanding is examined in the next section.

Before going further it is useful to emphasise a couple of points. First, because of its general nature, Menger’s explanation may be compatible with other scenarios.

For example, in distinct societies different commodities may have served some functions of money prior to the emergence of a generally accepted medium of exchange. Menger’s theory of saleability abstracts from the particularities of these societies and tells us that these commodities could be considered as goods with relatively high saleability. The development of market dependence, then, transforms some of these highly saleable goods into generally accepted media of exchange. Thus, Menger’s theory is general in the sense that it allows for the ex- istence of prior forms of money. In other words, existence of prior forms of money does not necessarily conflict with Menger’s explanation. Second, Menger’s story alerts us to the dynamics of market exchange as an important factor in explaining the origin of a generally acceptable medium of exchange. It is important to note here that none of the criticisms above object to (commercial) market exchange as an important factor in the evolution of a medium of exchange. Rather, they object to Menger’s description of the initial stage of the society, World (t), within which money emerges. Once we see the fact that Menger is trying to explain the origin of a generally acceptable medium of exchange, and that his emphasis is on market traffic and economic interests, we may see that Menger’s exposition studies the emergence of a medium of exchange in isolation from other factors. Third, it is possible to justify his approach by considering him as trying to show some of the mechanisms behind the origin of a medium of exchange – not all of them. In this interpretation, Menger’s explanation should not be considered as a full-fledged explanation of origin money, but as a partial potential (theoretical) explanation that presents a possible way in which some of the existent mechanisms may inter- act (or, may have interacted) in the process of emergence of money. These issues get more attention in the next section.

Source: Aydinonat N. Emrah (2008), The Invisible Hand in Economics: How Economists Explain Unintended Social Consequences, Routledge; 1st edition.