Broadly, we may test a model (verbal or analytical) in two ways: by asking wheth- er it is logically sound and by confronting it with the real world. The above mod- els ask whether Menger’s (or the classical) intuition about the origin of money is logically sound. They accomplish this in different ways:

- by focusing on particular aspects of it;

- by examining it under different conditions/assumptions;

- by applying different tools, or by using different methods.

Usually, 1, 2 and 3 go hand-in-hand. For example, Kiyotaki and Wright (1989) focus on storage costs and marketability in a three-good economy with three types of agents. They use equilibrium analysis as a tool for examining this environ- ment. Marimon et al. (1990) use ‘classifier systems’ and ‘computer simulations’ to examine the Kiyotaki–Wright environment with different specifications (i.e. by changing the number of goods, storage costs, etc.). Gintis (1997, 2000) simulates the behaviour of agents in the Kiyotaki–Wright environment, but he uses ideas from evolutionary theory to model the evolution of strategies. Luo (1999) changes the way in which daily trade is executed and by borrowing notions from evolution- ary biology, he introduces a mechanism of imitation. Young (1998), on the other hand, focuses on coordination by abstracting from the trading environment and from the complexities of production and consumption, and assumes that agents may learn from experience and change their strategies accordingly.

Presumably, all of these models have the ultimate aim of providing a better explanation of how money has emerged in history. Yet they simply do not go beyond examining or exploring their model worlds.34 Our examination of these models teaches us that we should not consider each and every model in econom- ics as providing new explanations, for sometimes they are explorations in model worlds. Sometimes, they do not tell us something new, but they just say that our old intuitions are likely to be correct, or incorrect. The motivations of the authors of the models of the emergence of a medium of exchange support this claim:

The basic goal of this project is to analyse a simple general equilibrium matching model, in which the objects that become media of exchange will be determined endogenously as a part of the non-cooperative equilibrium.

(Kiyotaki and Wright 1989: 928)

To be perfectly clear, the goal of the present paper is to use the sequential matching model to derive commodity and/or fiat money endogenously.

(Kiyotaki and Wright 1989: 930)

Here, the goal of Kiyotaki and Wright is not to provide the explanation of the emergence of money, rather, the authors want to understand whether money may be endogenously created in a certain type of framework: ‘The goal here is to cap- ture monetary exchange as an equilibrium phenomenon and not to force it onto the system’ (Kiyotaki and Wright 1991: 217). They ask whether it is possible that money is an unintended consequence of human action in this model world. Obvi- ously, Kiyotaki and Wright’s models teach us what we may consider as possible (and what we may not) under certain conditions. Yet they do not tell us whether these conditions were present in history or whether there are plausible mecha- nisms that may bring about this possibility. Similarly, Marimon et al. (1990) ex- plore the possibilities in the Kiyotaki–Wright environment.

Consider the changes from the Kiyotaki–Wright (1989) model to Marimon et al.’s (1990) simulation. Marimon et al. introduce AI agents instead of rational agents. The implicit question behind this change is the worry that Kiyotaki and Wright’s model may not hold if the model agents are not fully rational. Marimon et al. find that this worry is indeed true and that under the conditions specified by Kiyotaki and Wright, AI agents rarely use ‘speculative’ strategies and that usu- ally the least costly to store commodity emerges as a medium of exchange. The suggested improvement is obvious: AI agents are better approximations to real agents and it is more likely that Marimon et al.’s results hold in real world. Yet most of Marimon et al.’s results are inconclusive and are specific to certain model specifications. For this reason, it is hard to argue that there is much progress in un- derstanding how money is brought about as an unintended consequence of human action. Rather, we learn from this model that Kiyotaki and Wright’s results do not hold under every condition. If you like, this may be considered as progress in terms of removing unsound results from the Kiyotaki–Wright model. On the other hand, Marimon et al. demonstrate that even if individuals are not fully rational, commodity money may be brought about in the Kiyotaki–Wright environment. That is, they show that Kiyotaki and Wright’s results concerning fundamental equilibrium hold under more plausible assumptions about individual behaviour and that the fundamental equilibrium may be reached via simple learning dynam- ics.

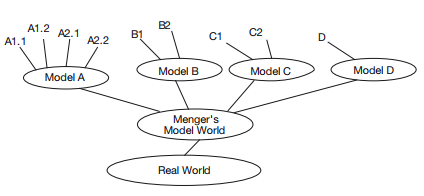

Figure 6.3 illustrates the relationship between Menger’s model world, Kiyo- taki–Wright models and Marimon et al.’s simulations: at the first level we have the real world, at the second level we have Menger’s rich but vague model. At the third level we have more idealised versions of Menger’s model world, Models A and B, which are examined by Kiyotaki and Wright, and Models C and D, which are considered by Marimon et al. in addition to Models A and B. Marimon et al. examines specific versions of these models, A.1.1, A.1.2, etc., which are par- ticular exemplifications of these models. Figure 6.3 shows how Menger’s model has been explored in the contemporary literature on emergence of a medium of exchange (also see Table 6.4).

Consider Young’s (1998: xi) goal of developing a new framework to examine the emergence and persistence of institutions (e.g. in our case, money). He states that his aim is (i) ‘to suggest a reorientation of game theory in which players are not hyper-rational and knowledge is incomplete’ and (ii) ‘to suggest how this framework can be applied to study of social and economic institutions.’ Young tries to get a better idea of what is possible by isolating his model from other problems and introducing a better approximation to the behaviour of real indi- viduals into the model. Yet he does not suggest that real individuals calculate the frequency distribution of the previous actions of a limited number of agents and calculate the best replies to this distribution. He rather suggests that if we may take this characterisation as an approximation to real individuals learning behaviour, then we may argue that individuals may be able to coordinate their behaviour. We have seen that his (and Schotter’s) model can only be considered as an account of the emergence of a medium of exchange, if considered together with Menger’s account. That is, he shows how individuals may be able to coor- dinate at a later stage in Menger’s model world. Figure 6.4 presents the relation between Menger’s account and Schotter and Young’s.

Figure 6.3 Models of emergence of money in relation to Menger’s model.

Schotter and Young present an idealised version of the last stages of Menger’s account of the emergence of money. They show how learning from past experi- ence makes coordination possible. We do not learn from these models how money actually emerged in history, rather we learn that it is plausible to argue that it may have emerged as an unintended consequence of human action.

After all of these models, we learn nothing new regarding the possible mecha- nisms that may explain the emergence of money (i.e. in comparison to Menger’s account), rather, we have a better understanding of the model worlds from which we may more confidently argue that money may be considered as an unintended consequence of human action. While this intuition is ‘tested’ on logical grounds to a considerable extent, the relation between the model world and the real world has not been examined in a meaningful way. There are few attempts to test these mod- els with real individuals (e.g. Duffy and Ochs’s 1999) and no attempts to verify whether the conditions under which money emerges in these model worlds hold in the real world. Unfortunately, it is hard to find information about the motivations of individuals and the particular conditions in which money may have flourished, and lack of this kind of evidence leaves us with partial potential explanations of the emergence of money.

Except Duffy and Ochs’s experiment, all models and simulations examined above deal with model worlds that are restricted versions of Menger’s model world (see Table 6.4). They examine the conditions under which we may con- sider money as an unintended consequence of human action, and the mechanisms and factors that may transform a world of direct exchange into a world where trade is mediated by money. For this reason, we may consider them as testing the logical soundness of the intuition that money may be an unintended consequence of human action. They do this by exploring the properties of an abstract world, by focusing on different aspects of an abstract trading environment, by adding elements to, or removing elements from this world. Some examine whether the ‘absence of double coincidence of wants’ would lead to a medium of exchange, some examine the effect of ‘transaction costs’, and some others examine whether the beliefs of individuals is important in the process of the emergence of money. Some other models examine what happens in a world where agents learn from past experience, or imitate others’ behaviour. But all these efforts are concerned with model worlds, or with variations of a model world.

Alternatively, we may say that these models contribute to the explanation of the emergence of a medium of exchange in these model worlds. Yet these models do not alert us to new explanatory mechanisms.36 Rather, these models show us that under certain conditions these factors and / or mechanisms may explain the emergence of a medium of exchange in the abstract world of models. They try to explicate how certain mechanisms, in isolation from others, may work together, or whether they are consistent with the existence of the explanandum phenomenon.

By logically testing and exploring the intuition that money may be considered as an unintended consequence of human action, they strengthen the belief in this intuition. They provide firmer grounds for arguing / believing that commodity money may be considered as an unintended consequence of human action. Nev- ertheless, we do not know – any better than Menger did – whether money was brought about by similar mechanisms in history.

When theoretical explanation is at stake, it is not usually easy to assess whether there is any ‘real’ explanatory progress unless the model that forms the basis of the explanation is applied to particular cases. As neither any of the above models nor their combination is used to explain particular cases, it is hard to asses the amount of progress in the economics literature on ‘the origin of money’. For this reason, it is useful to distinguish between actual explanatory progress and progress in potential explanatory power to discuss the contribution of these models, simula- tions and experiments.

Actual explanatory progress occurs when a particular case is ‘better’ explained with a new or improved model.37 For example, a singular explanation may be better than the other if it provides a better understanding of the actual and effec- tive causal mechanisms and structural relationships that are responsible for the particular fact or event (e.g. the emergence of money at a particular time period and place). These models do not provide such an explanation. For this reason, we may confidently argue that there is no actual explanatory progress.

Yet to have a better explanation of particular cases one may need a better col- lection of tools, models, theories, etc. Thus, if the research in one particular sub- ject develops in the line of providing better models that may guide us in the search for a good explanation, we may say that there is progress in terms of potential explanatory power. In isolation from each other, the above models, simulations and experiments contribute very little to what Menger has already said in terms of suggesting new possibilities. Yet we may have a better idea of what is accom- plished by these models by considering them in combination, as forming the parts of a meta-model (or theory) which is still under construction.38,39 Or, alternatively we may consider them as constituting the toolbox of economists when they are confronted with the task of explaining particular cases in the real world. Then we may see that the above models are giving more detailed pictures of particular areas of Menger’s model world. That is, by the introduction of new models that examine particular aspects of existing model worlds, the meta-model (or theory) of the emergence of money gets more detailed in time. Since particular models examine what may happen under certain conditions and assumptions, we obtain a more detailed picture of what is possible and how it is possible. This, of course, increases the potential applicability of the meta-model and its potential explana- tory power.

Source: Aydinonat N. Emrah (2008), The Invisible Hand in Economics: How Economists Explain Unintended Social Consequences, Routledge; 1st edition.