1. The work of the operating core

Here again we have a tightly knit configuration of the design parameters. Most important, the Professional Bureaucracy relies for coordination on the standardization of skills and its associated design parameter, training and indoctrination. It hires duly trained and indoctrinated specialists— professionals—for the operating core, and then gives them considerable control over their own work. In effect, the work is highly specialized in the horizontal dimension, but enlarged in the vertical one.

Control over his own work means that the professional works rela- tively independently of his colleagues, but closely with the clients he serves. For example, “the teacher works alone within the classroom, rela- tively hidden from colleagues and superiors, so that he has a broad discre- tionary jurisdiction within the boundaries of the classroom” (Bidwell, 1965:976). Likewise, many doctors treat their own patients, and accoun- tants maintain personal contact with the companies whose books they audit.

Most of the necessary coordination between the operating profes- sionals is then handled by the standardization of skills and knowledge—in effect, by what they have learned to expect from their colleagues. During an operation as long and as complex as open-heart surgery, “very little needs to be said [between the anesthesiologist and the surgeon] preceding chest opening and during the procedure on the heart itself: lines, beats and lights on equipment are indicative of what everyone is expected to do and does—operations are performed in absolute silence, particularly following the chest-opening phase” (Gosselin, 1978). The point is perhaps best made in reverse, by the cartoon that shows six surgeons standing around a patient on an operating table with one saying, “Who opens?” Similarly, the policy and marketing courses of the management school may be inte- grated without the two professors involved having even met. As long as the courses are standard, each knows more or less what the other teaches.

Just how standardized complex professional work can be is illustrated in a paper read by Spencer (1976) before a meeting of the International Cardiovascular Society. Spencer noted that “becoming a skillful clinical surgeon requires a long period of training, probably five or more years” (p. 1178). An important feature of that training is “repetitive practice” to evoke “an automatic reflex” (p. 1179). So automatic, in fact, that Spencer keeps his series of surgical “cookbooks,” in which he lists, even for “com- plex” operations, the essential steps as chains of thirty to forty symbols on a single sheet, to “be reviewed mentally in sixty to 120 seconds at some time during the day preceding the operation” (p. 1182). But no matter how standardized the knowledge and skills, their complexity ensures that con- siderable discretion remains in their application. No two professionals—no two surgeons or teachers or social workers—ever apply them in exactly the same way. Many judgments are required.

Training and indoctrination are a complicated affair in the Profes- sional Bureaucracy. The initial training typically takes place over a period of years in a university or special institution. Here the skills and knowledge of the profession are formally programmed into the would-be professional. But in many cases, that is only the first step, even if the most important one. There typically follows a long period of on-the-job training, such as internship in medicine and articling in accounting. Here the formal knowl- edge is applied and the practice of the skills perfected, under the close supervision of members of the profession. On-the-job training also com- pletes the process of indoctrination, which began during the formal teach- ing. Once this process is completed, the professional association typically examines the trainee to determine whether he has the requisite knowl- edge, skills, and norms to enter the profession. That is not to say, howev- er, that the person is “examined for the last time in his life, and is pro- nounced completely full,” such that “after this, no new ideas can be imparted to him,” as humorist and academic Stephen Leacock once com- mented about the Ph.D., the hurdle to entering the profession of univer- sity teaching. The entrance examination only tests the basic requirements at one point in time; the process of training continues. As new knowledge is generated and new skills develop, the professional upgrades his exper- tise. He reads the journals, attends the conferences, and perhaps also returns periodically for formal retraining.

2. The bureaucratic nature of the structure

All this training is geared to one goal—the internalization of standards that serve the client and coordinate the professional work. In other words, the structure of these organizations is essentially bureaucratic, its coordina- tion—like that of the Machine Bureaucracy—achieved by design, by stan- dards that predetermine what is to be done. Thus:

. . . obstetrics and gynecology is a relatively routine department, which even has something resembling an assembly (or deassembly?) line wherein the mother moves from room to room and nurse to nurse during the predictable course of her labor. It is also one of the hospital units most often accused of impersonality and depersonalization. For the mother, the birth is unique, but not for the doctor and the rest of the staff who go through this many times a day. (Perrow, 1970:74)

But the two kinds of bureaucracies differ markedly in the source of their standardization. Whereas the Machine Bureaucracy generates its own standards—its technostructure designing the work standards for its operators and its line managers enforcing them—the standards of the Professional Bureaucracy originate largely outside its own structure, in the self-governing associations its operators join with their colleagues from other Professional Bureaucracies. These associations set universal standards, which they make sure are taught by the universities and used by all the bureaucracies of the profession. So whereas the Machine Bu- reaucracy relies on authority of a hierarchical nature—the power of of- fice—the Professional Bureaucracy emphasizes authority of a profes- sional nature—the power of expertise.

The other forms of standardization are, in fact, difficult to rely on in the Professional Bureaucracy. The work processes themselves are too com- plex to be standardized directly by analysts. One need only try to imagine a work-study analyst following a cardiologist on his rounds or observing a teacher in a classroom in order to program the work. Similarly, the outputs of professional work cannot easily be measured and so do not lend them- selves to standardization. Imagine a planner trying to define a cure in psychiatry, the amount of learning that takes place in the classroom, or the quality of an accountant’s audit. Thus, Professional Bureaucracies cannot rely extensively on the formalization of professional work or on systems to plan and control it.

Much the same conclusion can be drawn for the two remaining coor- dinating mechanisms. Both direct supervision and mutual adjustment im- pede the professional’s close relationships with his clients. That relation- ship is predicated on a high degree of professional autonomy—freedom from having not only to respond to managerial orders but also to consult extensively with peers. In any event, the use of the other four coordinating mechanisms is precluded by the capacity of the standardization of skills to achieve a good deal of the coordination necessary in the operating core.

3. The pigeonholing process

To understand how the Professional Bureaucracy functions in its operat- ing core, it is helpful to think of it as a repertoire of standard programs— in effect, the set of skills the professionals stand ready to use—that are applied to predetermined situations, called contingencies, also standard- ized. As Weick (1976) notes of one case in point, “schools are in the business of building and maintaining categories” (p. 8). The process is sometimes known as pigeonholing. In this regard, the professional has two basic tasks: (1) to categorize the client’s need in terms of a contingency, which indicates which standard program to use, a task known as diag- nosis; and (2) to apply, or execute, that program. Pigeonholing simplifies matters enormously. “People are categorized and placed into pigeonholes because it would take enormous resources to treat every case as unique and requiring thorough analysis. Like stereotypes, categories allow us to move through the world without making continuous decisions at every moment” (Perrow, 1970:58). Thus, a psychiatrist examines the patient, declares him to be manic-depressive, and initiates psychotherapy. Similar- ly, a professor finds 100 students registered in his course and executes his lecture program; faced with twenty instead, he runs the class as a seminar. And the management consultant carries his own bag of standard acro- nymical tricks—MBO, MIS, LRP, PERT, OD. The client with project work gets PERT; the one with managerial conflicts, OD. Of course, clients often help out by categorizing themselves. As noted earlier, the person with an ingrown toenail does not visit a cardiologist; the student who wants to become a manager registers in the university’s business school.

Simon captures the spirit of pigeonholing with his comment, “The pleasure that the good professional experiences in his work is not simply a pleasure in handling difficult matters; it is a pleasure in using skillfully a well-stocked kit of well-designed tools to handle problems that are com- prehensible in their deep structure but unfamiliar in their detail” (1977:98). It is this pigeonholing process that enables the Professional Bureau- cracy to decouple its various operating tasks and assign them to individual, relatively autonomous professionals. Each can, instead of giving a great deal of attention to coordinating his work with his peers, focus on perfect- ing his skills. This is not to say that all uncertainty can be removed from the performance of the work, but only that attempts are made to contain what- ever uncertainty does remain in the jobs of single professionals. Focusing the uncertainty in this way is one of the reasons the professional requires considerable discretion in his work.

In the pigeonholing process, we see fundamental differences among the Machine Bureaucracy, the Professional Bureaucracy, and the Ad- hocracy. The Machine Bureaucracy is a single-purpose structure; presented with a stimulus, it executes its one standard sequence of programs, just as we kick when tapped on the knee. No diagnosis is involved. In the Profes- sional Bureaucracy, diagnosis is a fundamental task, but it is circum- scribed. The organization seeks to match a predetermined contingency to a standard program. Fully open-ended diagnosis—that which seeks a cre- ative solution to a unique problem—requires a third configuration, which we call Adhocracy. No standard contingencies or programs exist in that configuration.

It is an interesting characteristic of the Professional Bureaucracy that its pigeonholing process creates an equivalence in its structure between the functional and market bases for grouping. Because clients are categorized, or categorize themselves, in terms of the functional specialists who serve them, the structure of the Professional Bureaucracy becomes at the same time both a functional and a market-based one. Two illustrations help explain the point: A hospital gynecology department and a university chemistry department can be called functional because they group special- ists according to the knowledge, skills, and work processes they use, or market-based because each unit deals with its own unique types of cli- ents—women in the first case, chemistry students in the second. Thus, the distinction between functional and market bases for grouping breaks down in the special case of the Professional Bureaucracy.

4. Focus on the operating core

All the design parameters that we have discussed so far—the emphasis on the training of operators, their vertically enlarged jobs, the little use made of behavior formalization or planning and control systems—suggest that the operating core is the key part of the Professional Bureaucracy. The only other part that is fully elaborated is the support staff, but that is focused very much on serving the operating core. Given the high cost of the professionals, it makes sense to back them up with as much support as possible, to aid them and have others do whatever routine work can be formalized. Thus, universities have printing facilities, faculty clubs, alma mater funds, publishing houses, archives, athletics departments, libraries, computer facilities, and many, many other support units.

The technostructure and middle line of management are not highly elaborated in the Professional Bureaucracy. In other configurations (except Adhocracy), they coordinate the work of the operating core. But in the Professional Bureaucracy, they can do little to coordinate the operating work. Because the need for planning and the formalizing of the work of the professionals are very limited, there is little call for a technostructure (ex- cept, as we shall see, in the case of the nonprofessional support staff). In McGill University, for example, an institution with 17,000 students and 1,200 professors, the only units that could be identified by the author as technocratic were two small departments concerned with finance and bud- geting, a small planning office, and a center to develop the professors’ skills in pedagogy (the latter two fighting a continual uphill battle for acceptance). Likewise, the middle line in the Professional Bureaucracy is thin. With little need for direct supervision of the operators or mutual adjustment between them, the operating units can be very large, with few managers at the level of first-line supervisor, or, for that matter, above them. As noted earlier, the McGill Faculty of Management at the time of this writing functions effectively with sixty professors and a single manag- er, its dean.

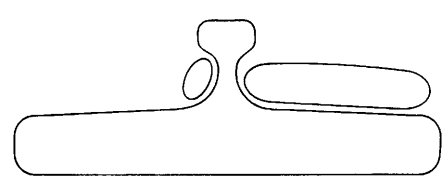

Figure 10-1. The Professional Bureaucracy

Thus, Figure 10-1 shows the Professional Bureaucracy, in terms of our logo, as a flat structure with a thin middle line, a tiny technostructure, and a fully elaborated support staff. All these characteristics are reflected in the organigram of McGill University, shown in Figure 10-2.

5. Decentralization in the professional bureaucracy

Everything we have seen so far tells us that the Professional Bureaucracy is a highly decentralized structure, in both the vertical and horizontal dimensions. A great deal of the power over the operating work rests at the bottom of the structure, with the professionals of the operating core. Often, each works with his own clients, subject only to the collective con- trol of his colleagues, who trained and indoctrinated him in the first place and thereafter reserve the right to censure him for malpractice.

The professional’s power derives from the fact that not only is his work too complex to be supervised by managers or standardized by ana- lysts, but also his services are typically in great demand. This gives the professional mobility, which enables him to insist on considerable autono- my in his work. When the professional does not get the autonomy he feels he requires, he is tempted to pick up his kit bag of skills and move on.

One is inclined to ask why professionals bother to join organizations in the first place. There are, in fact, a number of good reasons. For one thing, professionals can share resources, including support services, in a common organization. One surgeon cannot afford his own operating the- ater, so he shares it with others, just as professors share laboratories, lecture halls, libraries, and printing facilities. Organizing also brings the professionals together to learn from each other, and to train new recruits. Some professionals must join the organization to get clients. Although some physicians have their private patients, others receive them from the hospital emergency department or from in-patient referrals. Another rea- son professionals band together to form organizations is that the clients often need the services of more than one at the same time. An operation requires at least a surgeon, an anesthesiologist, and a nurse; an MBA program cannot be run with less than about a dozen different specialists. Finally, the bringing together of different types of professionals allows clients to be transferred between them when the initial diagnosis proves incorrect or the needs of the client change during execution. When the kidney patient develops heart trouble, that is no time to change hospitals in search of a cardiologist. Similarly, when an accountant finds his client needs tax advice, it is comforting to know that other departments in the same organization stand ready to provide the necessary service.

6. The administrative structure

What we have seen suggests that the Professional Bureaucracy is a highly democratic structure, at least for the professionals of the operating core. In fact, not only do the professionals control their own work, but they also seek collective control of the administrative decisions that affect them— decisions, for example, to hire colleagues, to promote them, and to dis- tribute resources. Controlling these decisions requires control of the mid- dle line of the organization, which professionals do by ensuring that it is staffed with “their own.” Some of the administrative work the operating professionals do themselves. Every university professor, for example, serves on committees of one kind or another to ensure that he retains some control over the decisions that affect his work. Moreover, full-time admin- istrators who wish to have any power at all in these structures must be certified members of the profession and preferably be elected by the pro- fessional operators, or at least appointed with their blessing. What emerges, therefore, is a rather demoocratic administrative structure.

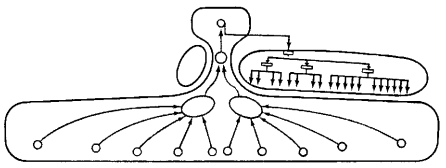

This administrative structure itself relies largely on mutual adjust- ment for coordination. Thus, the liaison devices, although uncommon in the operating core, are important design parameters in the middle line. Task forces and especially standing committees abound, as indicated in Figure 10-2; a number of positions are designated to integrate the admin- istrative efforts, as in the case of the ward manager in the hospital; and some Professional Bureaucracies even use matrix structure in admini- stration.

Because of the power of their operators, Professional Bureaucracies are sometimes called “collegial” organizations. In fact, some professionals like to describe them as inverse pyramids, with the professional operators at the top and the administrators down below to serve them—to ensure that the surgical facilities are kept clean and the classrooms well supplied with chalk. Such a description underestimates the power of the professional administrator—a point we shall return to shortly—but it seems to be an accurate description of the nonprofessional one—namely, the administra- tor who manages the support units. For the support staff—often much larger than the professional one, but charged largely with doing non- professional work—there is no democracy in the Professional Bureaucracy, only the oligarchy of the professionals. Support units, such as housekeep- ing or kitchen in the hospital or printing in the university, are as likely as not to be managed tightly from the top. They exist, in effect, as machine bureaucratic constellations within the Professional Bureaucracy.

What frequently emerge in the Professional Bureaucracy are parallel administrative hierarchies, one democratic and bottom-up for the profes- sionals, and a second machine bureaucratic and top-down for the support staff. In the professional hierarchy, power resides in expertise; one has influence by virtue of one’s knowledge and skills. In other words, a good deal of power remains at the bottom of the hierarchy, with the professional operators themselves. That does not, of course, preclude a pecking order among them. But it does require the pecking order to mirror the profes- sionals’ experience and expertise. As they gain experience and reputation, academics move through the ranks of lecturer, and then assistant, associ- ate, and full professor; and physicians enter the hospital as interns and move up to residents before they become members of the so-called medical staff. In fact, in many hospitals, this staff does not even report to the ex- ecutive director—the chief executive officer—but reports directly to the board of trustees. (Indeed, Charns (1976) reports that 41 percent of the physicians he surveyed in academic medical centers claimed they were responsible to no one!) In the nonprofession hierarchy, in contrast, power and status reside in administrative office; one salutes the stripes, not the man. Unlike the case in the professional structure, here one must practice administration, not a specialized function of the organization, to attain status. But “research indicates that a professional orientation toward ser- vice and a bureaucratic orientation toward disciplined compliance with procedures are opposite approaches toward work and often create conflict in organizations” (Blau, 1967-68:456). Hence, these two parallel hier- archies are kept quite independent of,each other, as shown in Figure 10-3.

7. The roles of the professional administrator

Where does all this leave the administrators of the professional hierarchy, the executive directors and chiefs of the hospitals and the presidents and deans of the universities? Are they powerless? Compared with their peers in the Simple Structure and the Machine Bureaucracy, they certainly lack a good deal of power. But that is far from the whole story. The professional administrator may not be able to control the professionals directly, but he does perform a series of roles that gives him considerable indirect power in the structure.

Figure 10-3. Parallel Hierarchies in the Professional Bureaucracy

First, the professional administrator spends much time handling dis- turbances in the structure. The pigeonholing process is an imperfect one at best, leading to all kinds of jurisdictional disputes between the profes- sionals. Who should teach the statistics course in the MBA program—the mathematics department or the business school? Who should perform mastectomies in hospitals—surgeons who specialize in operations or gynecologists who specialize in women? Seldom, however, can a senior administrator impose a solution on the professionals or units involved in a dispute. Rather, the unit managers—chiefs, deans, or whoever—must sit down together and negotiate a solution on behalf of their constituencies. Coordination problems also arise frequently between the two parallel hier- archies, and it often falls to the professional administrators to resolve them.

Second, the professional administrators—especially those at higher levels—serve key roles at the boundary of the organization, between the professionals inside and interested parties—governments, client associa- tions, and so on—on the outside. On the one hand, the administrators are expected to protect the professionals’ autonomy, to “buffer” them from external pressures. On the other hand, the administrators are expected to woo these outsiders to support the organization, both morally and finan- cially. Thus, the external roles of the manager—maintaining liaison con- tacts, acting as figurehead and spokesman in a public relations capacity, negotiating with outside agencies—emerge as primary ones in professional administration.

Some view the roles professional administrators are called upon to perform as signs of weakness. They see these people as the errand boys of the professionals, or else as pawns caught in various tugs of war—between one professional and another, between support staffer and professional, between outsider and professional. In fact, however, these roles are the very sources of administrator power. Power is, after all, gained at the locus of uncertainty. And that is exactly where the professional administrators sit. The administrator who succeeds in raising extra funds for his organiza- tion gains a say in how these are distributed. Similarly, the one who can reconcile conflicts in favor of his unit or who can effectively buffer the professionals from external influence becomes a valued—and therefore powerful—member of the organization.

Ironically, the professional becomes dependent on the effective ad- ministrator. The professional faces a fundamental dilemma. Frequently, he abhors administration, desiring only to be left alone to practice his profes-sion. But that freedom is gained only at the price of administrative effort— raising funds, resolving conflicts, buffering the demands of outsiders. This leaves the professional two choices: to do the administrative work himself, in which case he has less time to practice his profession, or to leave it to administrators, in which case he must surrender some of his power over decision making. And that power must be surrendered, it should be add- ed, to administrators who, by virtue of the fact that they do not wish to practice the profession, probably favor a different set of goals. Damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t. Take the case of the university professor oriented to research. To ensure the fullest support for research in his de- partment, he should involve himself in committees where questions of the commitment to teaching versus research are decided. But that takes time, specifically time away from research. What is the use of spending time protecting what one has no time left to do? So the professor is tempted to leave administration to full-time administrators, those who have expressed a lack of interest in research by virtue of seeking full-time administrative office.

We can conclude that power in these structures does flow to those professionals who care to devote effort to doing administrative instead of professional work, especially to those who do it well. But that, it should be stressed, is not laissez-faire power: the professional administrator keeps his power only as long as the professionals perceive him to be serving their interests effectively. The managers of the Professional Bu- reaucracy may be the weakest among those of the five configurations, but they are far from impotent. Individually, they are usually more powerful than individual professionals—the chief executive remaining the single most powerful member of the Professional Bureaucracy—even if that power can easily be overwhelmed by the collective power of the professionals.

8. Strategy formulation in the professional bureaucracy

A description of the strategy-formulation process in the Professional Bu- reaucracy perhaps best illustrates the two sides of the professional admin- istrator’s power. At the outset it should be noted that strategy takes on a very different form in these kinds of organizations. Since their outputs are difficult to measure, their goals cannot easily be agreed upon. So the no- tion of a strategy—a single, integrated pattern of decisions common to the entire organization—loses a good deal of its meaning in the Professional Bureaucracy.

Given the autonomy of each professional—his close working relation- ships with his clients, and his loose ones with his colleagues—it becomes logical to think in terms of a personal strategy for each professional. In many cases, each selects his own clients and his own methods of dealing with them—in effect, chooses his own product-market strategy. But pro- fessionals do not select their clients and methods at random. The profes- sionals are significantly constrained by the professional standards and skills they have learned. That is, the professional associations and training institutions outside the organization play a major role in determining the strategies that the professionals pursue. Thus, to an important extent, all organizations in a given profession exhibit similar strategies, imposed on them from the outside. These strategies—concerning what clients to serve and how—are inculcated in the professionals during their formal training and are modified as new needs emerge and as the new methods developed to cope with them gain acceptance by the professional associations. This outside control of strategy can sometimes be very direct: in one of the McGill studies, a hospital that refused to adopt a new method of treatment was, in effect, censured when one of the associations of medical specialists passed a resolution declaring failure to use it tantamount to malpractice.

We can conclude, therefore, that the strategies of the Professional Bureaucracy are largely ones of the individual professionals within the organization as well as of the professional associations on the outside. Largely, but not completely. There are still degrees of freedom that allow each organization within the profession to adapt the basic strategies to its own needs and interests. There are, for example, mental hospitals, wom- en’s hospitals, and veterans’ hospitals; all conform to standard medical practice, but each applies it to a different market that it has selected.

How do these organizational strategies develop? It would appear that the Professional Bureaucracy’s own strategies represent the cumulative effect over time of the projects, or strategic “initiatives,” that its members are able to convince it to undertake—to buy a new piece of equipment in a hospital, to establish a new degree program in a university, to develop a new specialty department in an accounting firm. Most of these initiatives are proposed by members of the operating core—by “professional en- trepreneurs” willing to expend the efforts needed to negotiate the accep- tance of new projects through the complex administrative structure (and if the method is new and controversial, through outside professional associa- tions as well).

What is the role of the professional administrator in all this? Certainly far from passive. As noted earlier, administration is neither the forte nor the interest of the operating professional. So he depends on the full-time administrator to help him negotiate his project through the system. For one thing, the administrator has time to worry about such matters. After all, administration is his job; he no longer practices the profession. For another, the administrator has a full knowledge of the administrative com- mittee system as well as many personal contacts within it, both of which are necessary to see a project through it. The administrator deals with the system every day; the professional entrepreneur may promote only one new project in his entire career. Finally, the administrator is more likely to have the requisite managerial skills—for example, those of negotiation and persuasion.

But the power of the effective administrator to influence strategy goes beyond helping the operating professionals. Every good manager seeks to change his organization in his own way, to alter its strategies to make it more effective. In the Professional Bureaucracy, this translates into a set of strategic initiatives that the administrator himself wishes to take. But in these structures—in principle, bottom-up—the administrator cannot im- pose his will on the professionals of the operating core. Instead, he must rely on his informal power, and apply it subtly. Knowing that the profes- sionals want nothing more than to be left alone, the administrator moves carefully—in incremental steps, each one hardly discernible. In this way, he may achieve over time changes that the professionals would have re- jected out of hand had they been proposed all at once.

Source: Mintzberg Henry (1992), Structure in Fives: Designing Effective Organizations, Pearson; 1st edition.