Jobs can be specialized in two dimensions. The first is “breadth” or “scope”—how many different tasks are contained in each and how broad or narrow is each of these tasks. At one extreme, the worker is a jack-of-all- trades, forever jumping from one broad task to another; at the other ex- treme, he focuses his efforts on the same highly specialized task, repeated day in and day out, even minute in and minute out. The second dimension of specialization relates to “depth,” to the control over the work. At one extreme, the worker merely does the work without any thought as to how or why; at the other, he controls every aspect of the work in addition to doing it. The first dimension may be called horizontal job specialization (in that it deals with parallel activities) and its opposite, horizontal job enlarge- ment; the second, vertical job specialization and vertical job enlargement.

1. Horizontal job specialization

Job specialization in the horizontal dimension—the predominant form of division of labor—is an inherent part of every organization, indeed every human activity. On a seal hunt, for example, the Gilyak eskimos divide their labor within the boat among harpooner, oarsman, and helmsman (Udy, 1959:91). In fact, the term “division of labor” dates back to the eighteenth century, when Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations. There he presented his famous example in which, even by 1776, “the division of labor has been very often taken notice of, the trade of the pin maker”:

One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the papers. . . (Smith, 1910:5)

Organizations so divide their labor—specialize their jobs—to increase productivity. Adam Smith noted that in one pin factory, ten men spe-zalized in their work were each able to turn out about 4,800 pins per day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they certainly could not each of them have made twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day . . .” (p. 5).

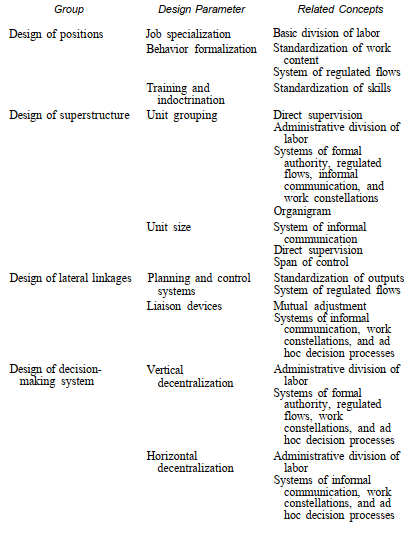

TABLE 2-1 . Design Parameters

What are the reasons for such productivity increases? Smith notes three: the improved dexterity of the workman from specializing in one task, the saving in time lost in switching tasks, and the development of new methods and machines that come from specialization. All three rea- sons point to the key factor that links specialization to productivity: repeti- tion. Horizontal specialization increases the repetition in the work, thereby facilitating its standardization. The outputs can be produced more uni- formly and more efficiently. Horizontal specialization also focuses the at- tention of the worker, which facilitates learning. A final reason for special- ization is that it allows the individual to be matched to the task. In Chapter 1 we noted that football teams put their slim players in the backfield, their squat players on the line. Likewise, Udy notes that the Gilyak eskimos put their best oarsmen toward the stern, their best shots in the bow.

2. Vertical job specialization

Vertical job specialization separates the performance of the work from the administration of it. Teaching offers a good example. Students who use workbooks or copy their lectures word for word have rather vertically specialized work—they simply carry out the activity. In contrast, when the students do projects, they assume control of much of the decision making in their work—their “jobs” become vertically enlarged, and they shift from passive responders to active participants. In the case of the pie filler, dis-‘ cussed in Chapter 1, his job was highly specialized in the vertical (as well as the horizontal) dimension. Alternatively, were he told to bake a pie to sell for $1.50 or, better still, had he owned a bakery and decided for himself what to bake and at what price, he could have been described as having a vertically enlarged job.

Organizations specialize jobs in the vertical dimension in the belief that a different perspective is required to determine how the work should be done. In particular, when a job is highly specialized in the horizontal dimension, the worker’s perspective is narrowed, making it difficult for him to relate his work to that of others. So control of the work is often passed to a manager with the overview necessary to coordinate the work by direct supervision or to an analyst who can do so by standardization. Thus, jobs must often be specialized vertically because they are specialized horizontally. But not always, as we shall soon see.

3. Job enlargement

Job specialization is hardly a panacea for the problems of position design; quite the contrary, job specialization creates a number of its own prob- lems, notably of communication and coordination. Consider a simple ex-ample, the way in which orders are taken in French and American restau- rants. In this respect, the work in many French restaurants is more specialized: the maitre d’hotel takes the order and writes it on a slip of paper, and the waiter serves it. In the American restaurant, the waiter generally does both tasks. Thus, if the customer in the French restaurant has a special request—for example, to have his coffee with his dessert instead of after it as is the norm in France—a communication problem arises. The maitre d’hotel must go to the trouble of telling the waiter or making a note on the slip of paper. (In fact, it is unlikely that he will do either, and it is left to the customer to try, often in vain, to get his message across to the waiter directly.) In effect, specialization creates problems of coordination. In more complex work, such as medicine, specialization has also been a mixed blessing. The great advances—for example, open-heart surgery, control of tuberculosis, transplants of various kinds—have been brought about by specialization in research and clinical work, but so too-as specialization placed all kinds of artificial barriers across the practice of medicine. Few doctors treat the body as an integrated system; rather, they treat clogged arteries, or emotional stress, or unhealthy diets.

High task specialization in the horizontal dimension also creates bal- ancing problems for the organization. If a barbershop designates one per- son to cut only children’s hair, it may face a situation in which adult customers are forced to wait while the children’s barber stands idle. Clear- ly size is an important factor here: A high volume of work facilitates high Horizontal specialization. Only the large barbershops can afford children’s specialists.

Another serious problem, especially in the operating core, is what high specialization in both dimensions can do to the worker—to his feel- ings about his work and his motivation to do it well. With the rise of Taylor’s Scientific Management movement after World War I, American industry (and, for that matter, Russian industry, too) became virtually obsessed with job specialization. “One has the feeling of division of labor having gone wild, far beyond any degree necessary for efficient produc- tion,” wrote James Worthy, an executive of Sears, Roebuck, in 1950 (p. 174). The belief that “all possible brain work should be removed from the shop floor and centered in the planning and laying out department” led to:ne most machinelike of jobs, as engineers sought to “minimize the charac- teristics of workers that most significantly differentiate them from ma- chines” (p. 67). All this, Worthy argues, “has been fantastically wasteful tor industry and society,” failing to make proper use of “management’s most valuable resource: the complex and multiple capacities of people.” Because “the meaning of work itself” was destroyed, people could only be treated as means; they could no longer exercise initiative. In place of intrin- sic motivation, workers had “to be enticed by rewards and threatened by punishments” (pp. 69, 70, 71).

Charlie Chaplin popularized the plight of the human robot in his pre-World War II film, Modern Times. But the problem has persisted to the present day. Only recently, however, with increasing worker alienation posing a direct threat to productivity itself, has there been a real thrust to change the situation. This has proceeded under the terms “job enlarge- ment,” for horizontal enlargement, and “job enrichment,” for vertical cou- pled with horizontal enlargement (Herzberg, 1968);1 more recently, all this has been subsumed under the broader title, “quality of working life,” now sufficiently in vogue to merit the acronym QWL. Here, for simplicity’s sake and to contrast with job specialization, we shall stay with the term “job enlargement,” whether horizontal or vertical.

In horizontal job enlargement, the worker engages in a wide variety of the tasks associated with producing products and services. He may either do more tasks in sequence, or do them one at a time, as before, but interchange tasks with his colleagues periodically so that his work becomes more varied. For example, in the assembly of the parts of a small motor, the assembly line may be eliminated and each worker may assemble the whole motor himself, or the workers may interchange positions on the assembly line periodically. When a job is enlarged vertically, or “en- riched,” not only does the worker carry out more tasks, but he also gains more control over them. For example, a group of workers may be given responsibility for the assembly of the motor, a natural unit of work, includ- ing the power to decide how the work will be shared and carried out.

Does job enlargement pay? The proponents say yes, and back up their conclusion with enthusiastic anecdotal reports. But more detached observers report failures as well as successes, and reviews of the research suggest that although the successes probably predominate, the overall results of job enlargement are mixed.

The results of job enlargement clearly depend on the job in question. To take two extreme examples, the enlargement of the job of a secretary who must type the same letter all day every day cannot help but improve things; in contrast, to enlarge the job of the general practitioner (one won- ders how—perhaps by including nursing or pharmacological tasks) could only frustrate the doctor and harm the patient. In other words, jobs can be too large as well as too narrow. So the success of any job redesign clearly depends on the job in question and how specialized it is in the first place. The natural tendency has, of course, been to select for redesign the nar- rowest, most monotonous of jobs, some specialized to almost pathological degrees, of which there has been no shortage in this industrialized world left to us by the followers of Frederick Taylor. Hence, we should not be surprised to find more successes than failures reported in this research.

That, however, should not lead to the conclusion that job enlargement is good per se.

There is also the question of tradeoffs inherent in any attempt to redesign a job. What the writings of people like Worthy have done is to introduce the human factor into the performance equation, alongside the purely technical concerns of the time-and-motion-study analysts. That has changed the equation: job enlargement pays to the extent that the gains from better-motivated workers in a particular job offset the losses from less than optimal technical specialization. Thus, like job specialization, job enlargement is hardly a panacea for the problems of position design; it is one design parameter among many, to be considered alongside the others.

So far, the question of whether job enlargement pays has been ad- dressed solely from the point of view of the organization. But the worker counts, too, as a human being who often deserves something better than a monotonous job. But here the research throws a curve, with its evidence that some workers prefer narrowly specialized, repetitive jobs. Nowhere is this point made clearer than in Stud Terkel’s fascinating book, Working (1972), in which all kinds of workers talk candidly about the work they do and their feelings about it. A clear message comes through: “One man’s meat is another man’s poison.” Occasionally, Terkel juxtaposes the com- ments of two workers in the same job, one who relishes it and another who detests it.

Why should the same routine job motivate one person and alienate another? Some researchers believe the answer relates to the age of the workers, others to where they live—older and urban workers having been shown in some studies to be more tolerant of narrow jobs. Others describe the differences in terms of Maslow’s (1954) “Needs Hierarchy Theory,” which orders human needs into a hierarchy of five groups—physiological, safety or security, love and belongingness, esteem or status, and self- actualization (to create, to fulfill oneself). The theory postulates that one group of needs becomes fully operative only when the next lower group is largely satisfied. In job design, the argument goes, people functioning at the lower end of the Maslow scale, most concerned with security needs and the like, prefer the specialized jobs, whereas those at the upper end, notably at the level of self-actualization, respond more favorably to en- larged jobs. Perhaps this explains why QWL has recently become such a big issue: with growing affluence and rising educational levels, the citizens of the more industrialized societies have been climbing up Maslow’s hier- archy. Their growing need for self-actualization can be met only in en- larged jobs. The equation continues to change.

4. Job specialization by part of the organization

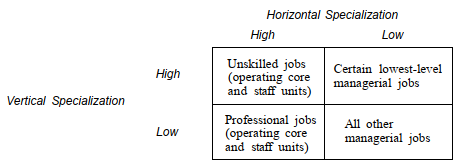

We would expect to find some relation between the specialization of jobs and their location in the organization. Productivity is more important in the operating core, where the basic products and services get produced; also, this is where the work is most repetitive. Hence, we would expect to find the most specialized jobs there, especially in the horizontal dimen- sion. In the vertical dimension, however, we would expect to find more variation. Many operators—such as those on assembly lines—perform the narrowest of jobs in both breadth and depth. These are the unskilled work- ers, on whom the job-enlargement programs have been concentrated. But other operators, because their specialized tasks are more complex, retain considerably control over them. In other words, their jobs are specialized horizontally but not vertically. Performing open-heart surgery, putting out fires in oil wells, and teaching retarded children all require considerable specialization, to master the skills and knowledge of the jobs. But the jobs are complex, requiring years of training, and that complexity precludes close managerial and technocratic control, thereby precluding vertical spe- cialization. Complex jobs, specialized horizontally but not vertically, are generally referred to as professional. And job enlargement is not an issue in these jobs, at least not from the perspective of the worker. Society tends to look very favorably on this kind of specialization; indeed, unskilled operators frequently try to have their jobs labeled “professional” to in- crease their status and reduce the controls imposed on them by the administrators.

Many of the same conclusions can be drawn for the staff units, both support and technocratic. Each support staff unit has a specialized function to perform—producing food in the plant cafeteria, fighting legal battles in the corporate legal office, and so on—with the result that support-staff jobs tend to be highly specialized in the horizontal dimension. How specialized they are in the vertical dimension depends, as it does for the operator’s jobs, on how complex or professional they are. In general, we would expect the support staffers of the lower echelons, such as those in the cafeterias, to have narrow, unskilled jobs subject to close control, and those at the high levels, such as in the legal office, to have more profes- sional jobs, specialized horizontally but not vertically. As for the analysts of the technostructure, they are professionals, in that their work requires considerable knowledge and skill. Hence, we would also expect their jobs to be specialized horizontally but not vertically. However, the technocratic clerks—those who apply the systems of standardization routinely—would tend to be less skilled and therefore have jobs specialized in both dimen- sions.

Managers at all levels appear to perform a basic set of interpersonal, informational, and decisional roles; in that sense, their work is specialized horizontally. But in a more fundamental sense, no true managerial job is specialized in the horizontal dimension. The roles managers perform are so varied, and so much switching is required among them in the course of any given day, that managerial jobs are typically the least specialized in the organization. Managers do not complain about repetition or boredom in their work, but rather about the lack of opportunity to concentrate on specific issues. This seems to be as true for foremen as it is for presidents. That is why attempts to redesign the job of chief executive generally move in the direction of job specialization, not enlargement—for example, by creating a chief executive office in which different people split up the top job of the organization. That such efforts have been successful is far from clear (see Mintzberg, 1973a:179-80,’for possible reasons why), and the job of CEO seems to remain as enlarged as ever.

TABLE 2-2. Job Specialization by Part of the Organization

Managerial jobs can differ in vertical specialization by level in the hierarchy. Whereas top managers generally have great discretion in their work, some first-line supervisors—notably assembly-line foremen, and su- pervisors of clerks and other unskilled workers—have highly circum- scribed jobs. Indeed, some of them are so subjected to the weight of au- thority and the standards of the technostructure that their jobs can hardly be called managerial at all.

Our conclusions about vertical and horizontal job specialization as a function of the part of the organization are summarized in Table 2-2.

Source: Mintzberg Henry (1992), Structure in Fives: Designing Effective Organizations, Pearson; 1st edition.