As indicated, this is not a linear process that begins with vision and ends with tactics. Instead, it is a continuous process in which vision contributes to capabilities, which contribute to tactics. Tactics in turn contribute to vision and capabilities. As will be discussed below, strategy is developed by a process of triangulation that copes with and creates market disruptions over and over again.

FIGURE 8-1

DISRUPTION AND THE NEW 7-S’s

Hypercompetitive firms are concerned with two forms of disruption—the one that comes from the outside into the firm and the one that comes from the inside out. In the former case, a change in the external environment occurs—brought on by competitors or the environment itself—and the firm must disrupt itself to respond to that change. In the latter case, the company moves in a preemptive strike to actively disrupt the environment and its competitors. It disrupts itself to disrupt the environment.

Both cases are examined below. Many hypercompetitive firms exhibit a combination of both forms of disruption. In the example of E. & J. Gallo Winery, for example, it experienced disruption from the outside from shifting tastes, demographics, and legal/social mores concerning alcohol consumption. It also created market disruption through its product deveb opment, marketing, and manufacturing strategies. The examples from Gallo Winery used below focus primarily on the outside forms of disruption and how Gallo overcame them, but Gallo created its share of market disruption as well.

In the competition between Komatsu and Caterpillar, Komatsu appears to have deliberately disrupted its larger competitor. This aggressive stance helped Komatsu seize the initiative until Caterpillar responded with its own attack to disrupt Komatsu.

1. Fast-flowing Wine: Disruptions in the Wine Industry

Gallo Wines is one of the largest and most successful wineries in the world, with annual sales of over one billion dollars and 28 percent of the U.S. wine market.1 Gallo accounts for one out of every three bottles of wine made in America2 At the time it was founded in 1933, Gallo was one of hundreds of small wineries that entered the market after the fall of Prohibition. While many of these small companies, and even some of the giants of that time, have since disappeared, Gallo has grown to dominate the industry.3 It is said jokingly that Gallo spills more wine than its competitors make. It has achieved this degree of dominance by disrupting its competitors and responding quickly to disruptions in its markets.

Gallo built its dominance over the wine market by building large-scale modern plants that were more like chemical processing plants at a time when its competitors treated wine making as an art form done in small batches. Gallo installed a mass-market and widespread distribution system that generated volume and captured economies of scale in an industry that thought small was better.

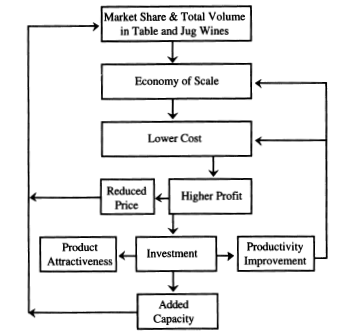

Gallo’s approach put into place a cycle, shown in Figure 8-2, that gobbled up more and more of the marketplace by constantly improving quality and lowering costs for low-end wines. Gallo moved from “street” wines (like Thunderbird) to jug wines to table wines over the decades. This cycle was sustained and expanded for many years until it was disrupted by external events that no longer allowed it to operate as effectively.

Gallo survived a severe disruption in the demographics and drinking habits of the American population in the mid- to late 1980s. It built its strong market for jug and table wine as the baby boom was growing up. Then that market was disrupted by the aging of the boomers. As their incomes rose and heavy drinking fell out of favor, the demand for inexpensive jug and table wines was replaced by a rush for high-quality varietal and other premium wines. Gallo was able to reshape itself to respond to this external disruption by disrupting its internal operations and approach to business to meet the changes of the market, first selling wine coolers and later selling varietals that required entirely different production, marketing, and product-development skills compared to those for jug and table wines. Through this pattern of disruption, Gallo continued to be a dominant player in the wine market, no matter what shape that market took.

FIGURE 8-2

THE “SUSTAINABLE” CYCLE CREATED BY GALLO WINERY’S LOW-COST PRODUCER STRATEGY

Based on William C. Waddell, The Outline of Strategy (Oxford, Ohio: The Planning Forum, 1986), p. 55.

As discussed in more detail below, Gallo used many of the New 7-S’s in creating and responding to disruption.

2. Skinning the Cat: Disruption in the Earth’moving Equipment Industry

In 1981 Caterpillar was the world’s largest manufacturer of earth-moving equipment, with sales close to nine billion dollars 4 Caterpillar controlled more than 50 percent of the world market for earth moving equipment. In just a few decades Komatsu had moved from being one of a multitude of small players to becoming the dominant company in Japan but still held only 16

percent of the 1981 world market. By 1984 Komatsu’s share of the world market had grown to 25 percent, and Caterpillar had dropped to 43 percent according to a Harvard Business School case study.5

Caterpillar had built its strengths upon a cycle of sustainable advantages, including its dependable quality, strong service and support, high global volume, which gave it economies of scale and lower costs, and high investments in R&D, which led to a full line of quality products. These quality products commanded a premium price, giving Caterpillar high margins that allowed the company to build a strong and loyal dealer network. This seemed to be an unstoppable perpetual-motion machine, as illustrated in Figure 8-3, which gobbled up more and more market share over time.

Komatsu set out to disrupt this perpetual-motion machine. It’s in-house slogan was Maru-C, which meant “encircle Caterpillar.”6 Komatsu took Caterpillar’s cycle of advantages apart piece by piece, disrupting the flow of the cycle in Figure 8-3 and shattering Cat’s advantages. Komatsu moved aggressively through the four arenas of competition, constantly moving to disrupt Caterpillar or maneuver around Caterpillar’s strategic strengths, as shown in Figure 8-4.

Komatsu rolled out one product after another into the world market, boosting quality up to or above Caterpillar’s standards and undercutting Cat’s prices. Komatsu focused on driving up quality first and then moved to drive down costs (competing in arena 1) on existing products in Caterpillar’s line. It started out gaining know-how through alliances with other u.s. firms, but then moved beyond Caterpillar’s existing line into aggressive development of new technology (arena 2). This gave it the power to expand into the geographic territory in Asia, Europe, and even Cat’s home turf of America. Komatsu also expanded its distribution channels from direct sales to dealers and then to regional centers (arena 3), especially in countries where Cat was not as strong as it was in the United States. Finally, it competed on resources, using its newly developed deep pockets for building overseas assembly plants, and entered into joint ventures to further expand its resources (arena 4).

FIGURE 8-3

CAT’S STRATEGY—SUSTAINING A PERPETUAL MOTION MACHINE

Based on research by Christopher Bartlett Key: EME = Earth Moving Equipment

FIGURE 8-4

KOMATSU: A STRATEGY OF DISRUPTION TO DERAIL

“THE PERPETUAL MOTION MACHINE”

Based on research by Chris Bartlett

In its rise to power, Komatsu used a series of actions that disrupted Caterpillar. However, Komatsu was also hit by external disruptions and Caterpillar’s disruptive responses.

Komatsu’s rise was slowed by an external disruption. In 1984 the Japanese juggernaut held 10 percent of the u.s. market and was poised to seize 20 percent of the market with plans to open a $21 million plant in Tennessee, according to a Harvard Business School case study. Then came an environmental disruption; In the last half of 1985, the dollar fell more than 20 percent against the yen. Komatsu, with most of its production based in Japan, announced price increases of 5 to 10 percent. Suddenly Caterpillar, which had been struggling to match Komatsu’s prices, was the low-cost producer. In an interview in Financial Times a Komatsu executive made overtures of reconciliation with its arch rival.7

Caterpillar could have responded by raising its prices and accommodating Komatsu. But when the yen fell again, it would be likely that Komatsu would not sustain its policy of reconciliation. Instead, Caterpillar seized the opportunity and held its price down, driving Komatsu back to 5 percent of the u.s. market and hurting it overseas.

If not for the shift in the value of the yen, Komatsu might have had an even more significant effect on Caterpillar’s u.s. market share. Komatsu used many of the New 7-S’s to disrupt Caterpillar, as will be discussed in more detail below.

Thus, Gallo and Komatsu used the New 7-S’s to respond to disruption from their competitors or other sources in their environments. They also used the New 7-S’s to actively disrupt their markets and their competitors.

The remainder of this chapter is dedicated to examining how the New 7-S’s can be used to create effective disruptions that seize the initiative for the disruptors. In particular, the next section looks at the criteria for envisioning a disruption that will create temporary advantage. Thereafter, the chapter looks at the resources, capabilities, and tactics needed to deliver the disruption with the greatest effect.

Source: D’aveni Richard A. (1994), Hypercompetition, Free Press.