Non-managerial theory of organizational power.

Organizations and enterprises are most appropriately run by co-operative agreement amongst those directly involved.

Collegialism is particulary associated with the professions, and is in that sense a form of middle class guild socialism.

It is contrasted with managerialism, which recommends placing control in a core of specialists who are not directly involved in whatever task the organization or profession performs.

Source:

Roger Scruton, A Dictionary of Political Thought (London,1982)

Definitions

1541: Spanish Conquistadors founding Santiago de Chile

Collins English Dictionary defines colonialism as “the policy and practice of a power in extending control over weaker peoples or areas”.[1] Webster’s Encyclopedic Dictionary defines colonialism as “the system or policy of a nation seeking to extend or retain its authority over other people or territories”.[3] The Merriam-Webster Dictionary offers four definitions, including “something characteristic of a colony” and “control by one power over a dependent area or people”.[9] Etymologically, the word “colony” comes from the Latin colōnia—”a place for agriculture”.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy uses the term “to describe the process of European settlement and political control over the rest of the world, including the Americas, Australia, and parts of Africa and Asia”. It discusses the distinction between colonialism, imperialism and conquest and states that “[t]he difficulty of defining colonialism stems from the fact that the term is often used as a synonym for imperialism. Both colonialism and imperialism were forms of conquest that were expected to benefit Europe economically and strategically,” and continues “given the difficulty of consistently distinguishing between the two terms, this entry will use colonialism broadly to refer to the project of European political domination from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries that ended with the national liberation movements of the 1960s”.[2]

In his preface to Jürgen Osterhammel’s Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview, Roger Tignor says “For Osterhammel, the essence of colonialism is the existence of colonies, which are by definition governed differently from other territories such as protectorates or informal spheres of influence.”[4] In the book, Osterhammel asks, “How can ‘colonialism’ be defined independently from ‘colony?'”[10] He settles on a three-sentence definition:

Colonialism is a relationship between an indigenous (or forcibly imported) majority and a minority of foreign invaders. The fundamental decisions affecting the lives of the colonised people are made and implemented by the colonial rulers in pursuit of interests that are often defined in a distant metropolis. Rejecting cultural compromises with the colonised population, the colonisers are convinced of their own superiority and their ordained mandate to rule.[11]

Types of colonialism

Dutch family in Java, 1927

Historians often distinguish between various overlapping forms of colonialism, which are classified[by whom?] into four types: settler colonialism, exploitation colonialism, surrogate colonialism, and internal colonialism.[12]

- Settler colonialism involves large-scale immigration, often motivated by religious, political, or economic reasons. It aims largely to replace any existing population. Here, a large number of people emigrate to the colony for the purpose of staying and cultivating the land.[12] Australia, Canada and the United States, all exemplify settler-colonial societies.[13][14][15]

- Exploitation colonialism involves fewer colonists and focuses on the exploitation of natural resources or population as labour, typically to the benefit of the metropole. This category includes trading posts as well as larger colonies where colonists would constitute much of the political and economic administration. Prior to the end of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and widespread abolition, when indigenous labour was unavailable, slaves were often imported to the Americas, first by the Portuguese, and later by the Spanish, Dutch, French and British.[citation needed]

- Surrogate colonialism involves a settlement project supported by a colonial power, in which most of the settlers do not come from a same ethnic group as the ruling power.

- Internal colonialism is a notion of uneven structural power between areas of a state. The source of exploitation comes from within the state. This is demonstrated in the way control and exploitation may pass from whites from the colonising country to a white immigrant population within a newly independent country.[16]

- National colonialism is a process involving elements of both settler and internal colonialism, in which nation-building and colonization are symbiotically connected, with the colonial regime seeking to remake the colonized peoples into their own cultural and political image. The goal is to integrate them into the state, but only as reflections of the state’s preferred culture. The Republic of China in Taiwan is the archetypal example of a national-colonialist society.[17]

Socio-cultural evolution

As colonialism often played out in pre-populated areas, sociocultural evolution included the formation of various ethnically hybrid populations. Colonialism gave rise to culturally and ethnically mixed populations such as the mestizos of the Americas, as well as racially divided populations such as those found in French Algeria or in Southern Rhodesia. In fact, everywhere where colonial powers established a consistent and continued presence, hybrid communities existed.

Notable examples in Asia include the Anglo-Burmese, Anglo-Indian, Burgher, Eurasian Singaporean, Filipino mestizo, Kristang and Macanese peoples. In the Dutch East Indies (later Indonesia) the vast majority of “Dutch” settlers were in fact Eurasians known as Indo-Europeans, formally belonging to the European legal class in the colony (see also Indos in pre-colonial history and Indos in colonial history).[18][19]

History

-

Map of colonial and land-based empires throughout the world in 1800 CE.

-

Map of colonial and land-based empires throughout the world in 1914 CE.

-

Map of colonial empires (and Soviet Union) throughout the world in 1936 CE.

-

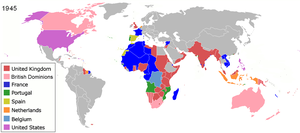

Map of colonial empires at the end of the Second World War, 1945 CE.

Ibrahim Muteferrika, Rational basis for the Politics of Nations (1731)[20]

Premodern

Activity that could be called colonialism has a long history starting with the Egyptians. Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans also built colonies in antiquity. Phoenicia was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550 BC to 300 BC and later the Persian empire and Greek Empire continued on this line of setting up colonies. The Romans would soon follow, setting up colonies throughout the Mediterranean, Northern Africa, and Western Asia. Beginning in the 7th century, Arabs colonized a substantial portion of the Middle East, Northern Africa, and parts of Asia and Europe. In the 9th century a new wave of Mediterranean colonisation had begun between competing states such as the Venetians, Genovese and Amalfians, invading the wealthy previously Byzantine or Eastern Roman islands and lands. Venice began with the conquest of Dalmatia and reached its greatest nominal extent at the conclusion of the Fourth Crusade in 1204, with the declaration of the acquisition of three octaves of the Byzantine Empire.[21]

Modern

Iberian Union of Spain and Portugal between 1580 and 1640

Modern colonialism started with the Portuguese Prince Henry the Navigator, initiating the Age of Exploration. Spain (initially the Crown of Castile) and soon later Portugal encountered the Americas through sea travel and built trading posts or conquered large extensions of land. For some people, it is this building of colonies across oceans that differentiates colonialism from other types of expansionism. These new lands were divided between the Spanish Empire and Portuguese Empire.[22]

The 17th century saw the creation of the French colonial empire and the Dutch Empire, as well as the English overseas possessions, which later became the British Empire. It also saw the establishment of a Danish colonial empire and some Swedish overseas colonies.[23]

A first wave of independence was started by the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), initiating a new phase for the British Empire.[24] The Spanish Empire largely collapsed in the Americas with the Latin American wars of independence. However, many new colonies were established after this time, including the German colonial empire and Belgian colonial empire. In the late 19th century, many European powers were involved in the Scramble for Africa.[25]

The Russian Empire, Ottoman Empire and Austrian Empire existed at the same time as the above empires but did not expand over oceans. Rather, these empires expanded through the more traditional route of the conquest of neighbouring territories. There was, though, some Russian colonisation of the Americas across the Bering Strait. The Empire of Japan modelled itself on European colonial empires. Argentina and the Empire of Brazil fought for hegemony in South America. The United States of America gained overseas territories after the Spanish–American War for which the term “American Empire” was coined.[26]

Map of the British Empire (as of 1910)

After the First World War, the victorious allies divided up the German colonial empire and much of the Ottoman Empire between themselves as League of Nations mandates. These territories were divided into three classes according to how quickly it was deemed that they would be ready for independence. The empires of Russia and Austria also collapsed.[27]

After World War II decolonisation progressed rapidly. This was caused by a number of reasons. First, the Japanese victories in the Pacific War showed Indians and other subject peoples that the colonial powers were not invincible. Second, all the colonial powers were significantly weakened by World War II.[28]

Dozens of independence movements and global political solidarity projects such as the Non-Aligned Movement were instrumental in the decolonisation efforts of former colonies. These included significant wars of independence fought in Indonesia, Vietnam, Algeria, and Kenya. Eventually, the European powers—pressured by the United States and Soviets—resigned themselves to decolonisation.

In 1962 the United Nations set up a Special Committee on Decolonisation, often called the Committee of 24, to encourage this process.

The status and cost of European colonization at the turn of the 20th century

Colonial Governor of the Seychelles inspecting police guard of honour in 1972

The world’s colonial population at the time of the First World War totalled about 560 million people, of whom 70% were in British possessions, 10% in French possessions, 9% in Dutch possessions, 4% in Japanese possessions, 2% in German possessions, 2% in American possessions, 2% in Portuguese possessions, 1% in Belgian possessions and 1/2 of 1% in Italian possessions. The domestic domains of the colonial powers had a total population of about 370 million people.[29]

Asking whether colonies paid, economic historian Grover Clark argues an emphatic “No!” He reports that in every case the support cost, especially the military system necessary to support and defend the colonies outran the total trade they produced. Apart from the British Empire, they were not favoured destinations for the immigration of surplus populations.[30] The question of whether colonies paid is, however, a complicated one when recognizing the multiplicity of interests involved. In some cases colonial powers were paying a lot in military costs, while the benefits could be pocketed by private investors. In other cases the colonial powers managed to move the burden of administrative costs to the colonies themselves by imposing taxes.[31]

Neocolonialism

The term neocolonialism has been used to refer to a variety of contexts since decolonisation that took place after World War II. Generally it does not refer to a type of direct colonisation, rather, colonialism by other means. Specifically, neocolonialism refers to the theory that former or existing economic relationships, such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the Central American Free Trade Agreement, or through companies (such as Royal Dutch Shell in Nigeria and Brunei) created by former colonial powers were or are used to maintain control of their former colonies and dependencies after the colonial independence movements of the post–World War II period.

The term was popular in ex-colonies in the late 20th century.

I’m impressed, I need to say. Actually rarely do I encounter a blog that’s both educative and entertaining, and let me inform you, you may have hit the nail on the head. Your concept is outstanding; the difficulty is one thing that not sufficient people are speaking intelligently about. I’m very glad that I stumbled throughout this in my seek for something relating to this.