So far we have focused on the fact that the functional de- partments in these six organizations had developed differentiated attributes that seemed to be related to their overall effectiveness. There is, however, another side to these differences in orientations and organizational practices. They also mean that when it becomes necessary to make joint decisions, managers from different departments will approach the problem from different frames of references and may have difficulty in collaborating effectively. We now want to learn whether there was a systematic relationship between the degree of differentiation between any two departments and their ability to achieve effective integration. We have already mentioned in general terms the requirements in this industry for close integration of the basic functional units, but we must now look more closely at these requirements to set the stage for testing the relationship between differentiation and integration.

1. Required Integration

The top executives interviewed about conditions in this environment indicated that the focus on innovation as a dominant issue created the requirement for two especially critical interdependencies among departments. One of them stated it this way:

I would have a difficult time distinguishing where [be-tween sales and research or between production and research] it is necessary to obtain the most coordination, but it does seem to me that there is a sequence which it is helpful to understand. First, it is necessary to have contact between research and the people in contact with the customers. They spend a long time together working on the initial stage of development. They work together deciding what the cus- tomer needs and in testing the product in the customer’s shop. Finally, the production people are brought in, when the process is ready to be handed over to them. How soon they are brought in would depend upon whether equipment modifications would be necessary. The research people then have to work out the processing problems with them.

As this executive points out, the sales and research units in any organization in this industry were required to work closely together and to make complicated joint decisions. This tight connection was necessary because the problems of testing and introducing a newly developed or modified material required the combined efforts of marketing personnel and research scientists and engineers. The high degree of integration between the research and production units was necessary to inform research scientists about technical problems that they might be able to overcome; to acquaint production personnel with new processing techniques that could be introduced; and to determine what technological innovations were possible and desirable.

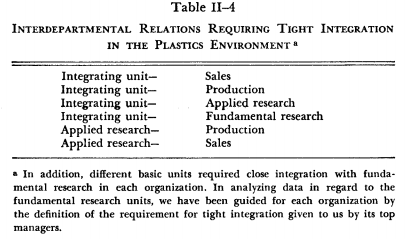

We have been discussing these relationships between pro- duction and research and sales and research units as if there were only one research department in each organization. Since each actually had two research units, this complicates the problem of establishing where close integration was required. This is especially so because of differences in the tasks assigned to the applied research unit in the six organizations. In some, the applied laboratories were conducting long- range research similar to that carried on in the fundamental laboratories. In others, the applied laboratories dealt with more certain problems, such as short-term process improvements and customer technical service. This meant that although the applied research units in all six organizations had to be closely integrated with both sales and production, there were some variations in which basic units were required to work closely with fundamental research. For example, in some organizations close integration was required between applied research and fundamental research, as well as between fundamental research and production, while in other organizations the only basic unit requiring close integration with fundamental research was production. In only one organization did the executives indicate a requirement that sales and fundamental research be closely integrated.

One other factor complicated determining the points within these organizations where close integration was required: All six organizations had established a group or department of “integrators,” whose responsibility was primarily to facilitate collaboration among the middle and lower managers in the basic units. According to all of the top managers, close integration was required among these “integrating units” and all four basic units.

While these are the relationships where close integration of functional units is required, the top managers interviewed were not suggesting that the sales-production relationship was not important. Rather, the coordination required here could be more nearly routine, since it generally dealt with relatively nonproblematical operational issues of customer delivery and schedules.

The major interdepartmental relationships in which close integration was required in this environment are summarized in Table II-4. As we have already seen, these same units that had to work closely together also had to be quite different from one another. This poses two fundamental questions, which will interest us throughout the book. Do great differences among departments in ways of thinking and in organizational practice generate problems in achieving integration? If this is the case, how do effectively competing organizations obtain both the required state of differentiation and the required state of integration?

2. Inverse Relation Between Differentiation and Integration

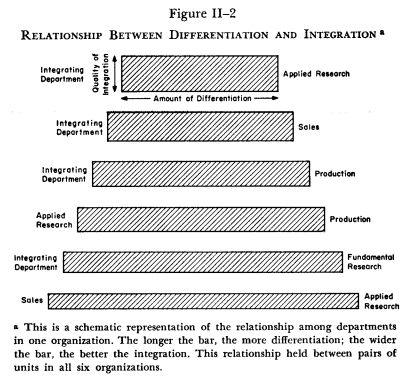

Based on earlier behavioral studies, as we suggested above, we predicted that there would be an inverse relation between the degree of differentiation between any two departments in a single organization and the quality of the integration be-tween them. When we tested for this, we did in fact find in all six organizations a very clear inverse relationship between the magnitude of differences in orentations and structure be-tween pairs of departments and the effectiveness of integra-tion between them. (This relationship is schematically rep-resented in Figure II-2.) The more similar two departments were in structure an in the orientations of their personnel, the more effective was the integration between them. Con-versely, the more different two departments were in these at-tributes, the more difficulties they were having in achieving integration. (This relationship was statistically significant in five of the organizations at .01 and in the sixth at .05, using Spearman’s coefficient of rank-order correlation.) In essence, the degree of differentiation among departments within each organization was antagonistic to the quality of integration ob-tained.

Given this finding, we could logically expect, in comparing the states of differentiation and integration among organizations, to find that the more highly differentiated all the units in the organizations were, the more difficulty the organization would have in achieving high-quality integration. If this were the case, we wondered if it would be at all possible for organizations simultaneously to achieve both the high degree of differentiation and the tight integration that the top managers of these organizations had told us were required for successful performance in this industry.

Source: Lawrence Paul R., Lorsch Jay W. (1967), Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration, Harvard Business School.