According to Scott (2008), institutional theory is “a widely accepted theoretical posture that emphasizes rational myths, isomorphism, and legitimacy.” Researchers building on this perspective emphasize that a key insight of institutional theory is imitation: rather than necessarily optimizing their decisions, practices, and structures, organizations look to their peers for cues to appropriate behavior.

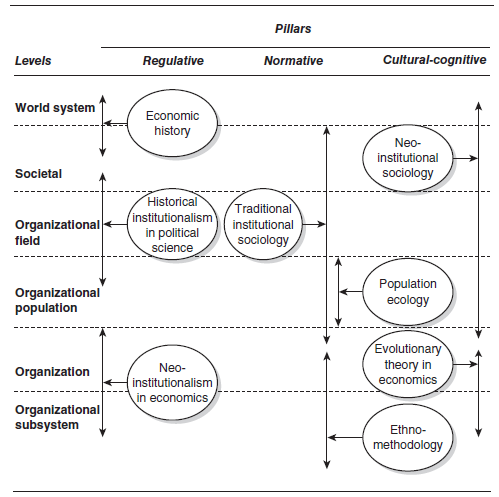

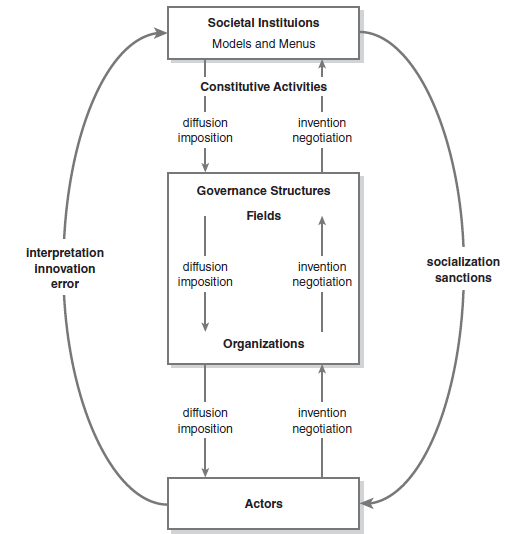

In defining institutions, according to William Richard Scott (1995, 235), there is “no single and universally agreed definition of an ‘institution’ in the institutional school of thought.” Scott (1995:33, 2001:48) asserts that: “Institutions are social structures that have attained a high degree of resilience. [They] are composed of cultural-cognitive, normative, and regulative elements that, together with associated activities and resources, provide stability and meaning to social life. Institutions are transmitted by various types of carriers, including symbolic systems, relational systems, routines, and artifacts. Institutions operate at different levels of jurisdiction, from the world system to localized interpersonal relationships. Institutions by definition connote stability but are subject to change processes, both incremental and discontinuous.”

There are two dominant trends in institutional theory: Old institutionalism and New institutionalism

Main contentsSee more

Powell and DiMaggio (1991) define an emerging perspective in sociology and organizational studies, which they term the ‘new institutionalism’, as rejecting the rational-actor models of Classical economics. Instead, it seeks cognitive and cultural explanations of social and organizational phenomena by considering the properties of supra-individual units of analysis that cannot be reduced to aggregations or direct consequences of individuals’ attributes or motives.

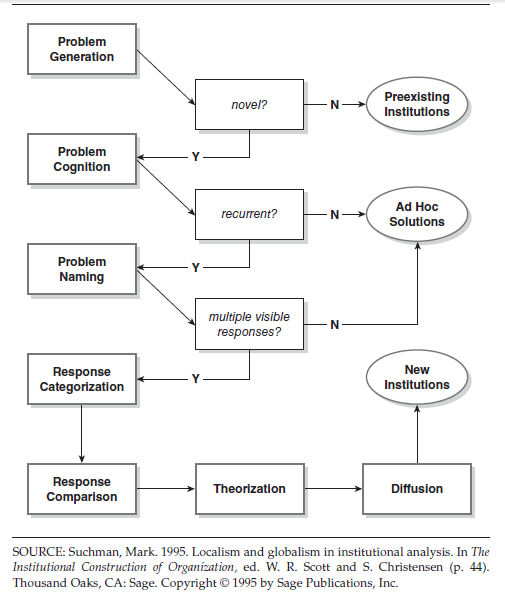

Scott (1995) indicates that, in order to survive, organisations must conform to the rules and belief systems prevailing in the environment (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983; Meyer and Rowan, 1977), because institutional isomorphism, both structural and procedural, will earn the organisation legitimacy (Dacin, 1997; Deephouse, 1996; Suchman, 1995). For instance, multinational corporations (MNCs) operating in different countries with varying institutional environments will face diverse pressures. Some of those pressures in host and home institutional environments are testified to exert fundamental influences on competitive strategy (Martinsons, 1993; Porter, 1990) and human resource management (HRM) practices (Rosenzweig and Singh, 1991; Zaheer, 1995). Corporations also face institutional pressures from their most important peers: peers in their industry and peers in their local (headquarters) community; for example, Marquis and Tilcsik (2016) show that corporate philanthropic donations are largely driven by isomorphic pressures that companies experience from their industry peers and local peers. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and social organizations can also be susceptible to isomorphic pressures.

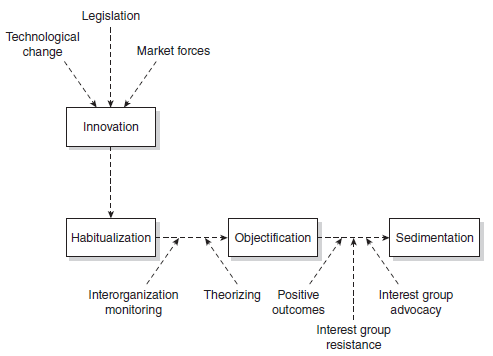

More recent work in the field of institutional theory has led to the emergence of new concepts such as

– institutional logics, a concept pioneered by Friedland & Alford (1991) and later by Thornton, Ocasio & Lounsbury (2012). The institutional logic perspective mostly take a structural and macro approach to institutional analysis

– institutional work, a concept pioneered by Lawrence & Suddaby, (2006). By contrast with the logic perspective, it gives agentic power to social actors, and assumes those actors can influence institutions – either maintaining or disrupting them.

There is substantial evidence that firms in different types of economies react differently to similar challenges (Knetter, 1989). Social, economic, and political factors constitute an institutional structure of a particular environment which provides firms with advantages for engaging in specific types of activities there. Businesses tend to perform more efficiently if they receive the institutional support.