1. Organizational Performance

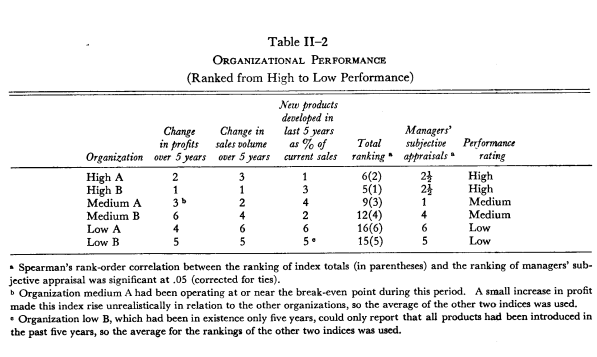

We did not, we must stress, pre-select these organizations on the basis of their performance, since the required information was not public. We did, however, try to choose organizations with a general reputation for being either highly successful or somewhat less effective. As it turned out, based on the measures of performance we obtained, we did achieve a balance of highly effective organizations and those with problems in achieving long- term success. The six organizations were ranked in terms of three performance measures: change in profits over the past five years; change in sales volume over the past five years; and new products introduced in the past five years as a percent of current sales (Table II—2). The total ranking of these variables gave us one measure of performance, but we felt it was also necessary to check this index by obtaining from the chief executive in each organization a subjective appraisal of how well his organization was doing as compared to what he would like. The rank order of this subjective appraisal correlated closely with our total performance index, which gave us some assurance that we were obtaining at least a crude measure of relative performance.

As a further check on these performance measures, we also interviewed the top two or three executives in each organization to learn their views about how well each company was doing. The information gathered in these interviews, which was consistent with that reported in Table II—2, also suggested that the six organizations did cover a wide range of performance.

In both high-performing organizations the top executives interviewed were highly satisfied with the way things were going. They were pleased with past and current performance, and felt that the future looked even more promising. Top managers in the medium-performing organizations were less enthusiastic in appraising performance. In medium A the executives reported that they had been through a difficult period, but that in the current year the organization had begun an upward trend, which needed even greater improvement.1 (This recent shift to a more favorable performance probably accounted for the fact that its chief executive rated this organization’s performance closer to ideal than did the chief executive in any other organization. As Table II—2 indicates, this was the only important deviation of the top managers’ appraisal from our index. This man’s enthusiasm was understandable, but according to our evidence, not completely accurate.) The situation for medium-performing organization B was similar to that at organization A. Five to ten years be-fore this study was made it had been an industry leader. Its position had slipped, but at the time of the study its top man- agement felt that the unfavorable trend had been reversed. Again, there was a feeling that there was room for further improvement, but also the belief that the performance trend was in the right direction.

The low-performing organizations were both characterized by their top administrators as having serious difficulty in dealing with this environment. They had not been successful in introducing and marketing new products. In fact, their attempts to do so had met with repeated failures. This record, plus other measures of performance available to top management, left them with a feeling of disquiet and a sense of urgency to find ways of improving their performance.

From these interviews, the top managers’ subjective ap- praisals, and the empirical evidence available, we felt justified in dividing these six organizations into the three broad categories of performance that we have indicated. With this general understanding of how these organizations were succeeding in dealing with the plastics industry environment, we can now examine their internal functioning to learn if their state of differentiation was related to effective performance.

2. Differentiation and Performance

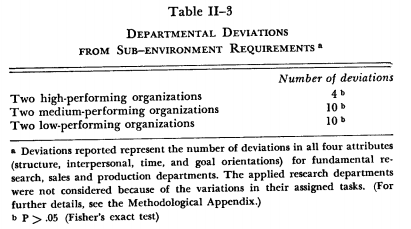

We have seen that the structures and interpersonal, time, and goal orientations of the functional units in all six organizations were generally different and that this differentiation was usually consistent with the requirements of their different sub- environments. Some units in some of the organizations, however, had not fully developed the attributes that we predicted would be required to deal with their part of the environment. This demonstrates the point made earlier that the achievement of the required state of differentiation was problematical. Organizational practices and orientations that fit the task requirements do not necessarily emerge in all depart-ments. Why this fit occurs in some situations and not in others is a complex question that cannot yet be answered. We were, however, interested in learning whether the attributes of functional departments tended more to fit the requirements of their part of the environments in the high-performing organizations than in the less effective ones.

This, in fact, turned out to be the case (Table II—3). The units in the high-performing organizations deviated from their environmental requirements significantly less than did departments in either the medium- or low-performing firms. This suggests that the achievement of a degree of differentiation consistent with the requirements of the environment is related to the organization’s ability to cope effectively with its environment.

When personnel in a particular department share attitudes and interests that focus clearly on departmental goals and have time horizons consistent with their task, they will be more effective. Similarly, when they have developed interpersonal modes that are appropriate to the nature of their work, their performance should be effective. Organizational practices that provide a degree of latitude or control consistent with the nature of the task will also facilitate the department’s dealings with its part of the environment.

Source: Lawrence Paul R., Lorsch Jay W. (1967), Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration, Harvard Business School.