Most of the models of ‘the origin of money’ are based on, or related to the Kiyo- taki–Wright (1989) model that focuses on the existence of an equilibrium where model agents use a certain commodity as a medium of exchange. For this reason it is important to have a fine grasp of the Kiyotaki–Wright environment and its rela- tion to Menger’s account. This section starts with a description of the Kiyotaki– Wright model and examines the related models. First, the results concerning the existence of commodity money and then the existence of fiat money equilibrium is examined.

1. The existence of commodity money equilibrium

Kiyotaki and Wright (1989) present a model economy where there are three com- modities (1, 2, 3) and three types of agents (I, II, III). Type I agents consume commodity 1, type II agents consume commodity 2, and type III agents consume commodity 3. No agent produces what he consumes. Thus, to be able to consume (e.g. to eat) they have to exchange their production good with their consumption good – that is, they are market dependent. It is assumed that every agent can only store one commodity at a time, and storing is costly. The storage costs of com- modities are different for different types of agents. If we define the cost of storing good j for type i as cij, then the following condition holds: cii3> ci2 > ci1.

The agents meet (in pairs) randomly at the marketplace, and when they meet, they have to decide whether or not to exchange their inventories. Exchange entails one-for-one swap of inventories. If an agent is able to acquire his consumption good at the market, he immediately consumes it and produces one unit of his pro- duction good. If an agent decides to exchange his inventory with a good he cannot consume, he stores it and waits for the next exchange opportunity to exchange it with his consumption good. Because of these specifications, in every period there are always agents who are facing the double coincidence of wants problem. Every individual is assumed to choose a trading strategy that would maximise his expected discounted utility, which is dependent on the utility of consumption, disutility of production and storage, and a discount factor (see Appendix II). Trad- ing strategies are rules that determine whether one agent is willing to exchange his inventory with another agent. Ideally, a trading strategy should depend on the trading history of the agent. Yet Kiyotaki and Wright isolate their model from the influence of time and of agents’ trading history. They only focus on the invento- ries of the trading agents, on the storing costs and on the economising actions of the agents. The strategies of the agents depend on a comparison of the indirect utility of storing the current inventory and exchanging it with another good. If a type i agent is able to exchange his inventory, good k, with his consumption good i* (k # i*), he always does it. But if he matches with an agent who has in inventory a good j (j # i*, k # j) that he cannot consume, the agent takes a decision, given the storage costs of j and k, and his expectations. That is, if the agent expects it to be easier to exchange j with i* in the next period than exchanging k with i*, then he is willing to exchange k with j, given that the storage cost of j is sufficiently low. Trade occurs if both agents are willing to exchange k with j.

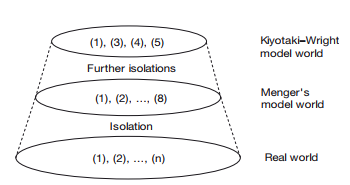

Given the assumptions of the Kiyotaki–Wright (1989) model we may examine the way in which it is related to Menger’s model world (see Figure 6.1). In the real world there may be many factors that may be effective in the process of the emergence of a medium of exchange. We have seen that Menger focuses on some of them by isolating the influence of others. Particularly, Menger focuses on a set of explanantia, which consists of:

- economising actions;

- discovery, learning and imitation;

- absence of double coincidence of wants;

- storage costs;

- marketability5;

- expectations of individuals;

- frequency of use; and

- availability of goods.

Roughly, saleability of a good is influenced by the following set of factors: {4,5, 6, 7, 8}. Kiyotaki and Wright (1989) make further isolations to examine the existence of a monetary equilibrium, as shown in Figure 6.1.6 That is, they focus on a subset of the factors in Menger’s model world, particularly on 1, 3, 4 and 5. In this manner, their model is much more specific.

Figure 6.1 Kiyotaki–Wright model vs. Menger’s model.

Kiyotaki and Wright analyse the existence of equilibrium for two different economies, Model A and Model B, in this isolated environment. The only differ- ence between the two models is the characterisation of agent types in terms of what they produce, as seen in Table 6.1.

For Model A, Kiyotaki and Wright (1989: 934–935) determine two types of equilibrium for different parameter values:

- A fundamental equilibrium where every agent ‘prefers a lower-storage-cost commodity to a higher-storage-cost commodity unless the latter is their own consumption good’.

- A speculative equilibrium where agents ‘sometimes trade a lower- for higher- storage-cost commodity [. . .] because they rationally expect that this is the best way to trade for another good that they do want to consume, that is, because it is more marketable’.

Kiyotaki and Wright find that for both economies there is an equilibrium where all agents use fundamental strategies and where commodity money exists. They also find that for certain parameter values some agents speculate and there is an equilibrium where both low-storage-cost and high-storage-cost goods serve as media of exchange. That is, they find that commodity money equilibrium is a possible state of the model world (i.e. H(1) confirmed). However, they do not tell how this model economy is transformed from a state of unmediated exchange to a state with a medium of exchange. Moreover, they do not tell why agents should believe that a certain good is more marketable. They only show that if they expect that a high-storage-cost good is more marketable, then (under some conditions) they will use it as a medium of exchange.

Starr (1999) obtains similar results to that of Kiyotaki and Wright (1989). He presents two different models that examine the importance of ‘absence of dou- ble coincidence of wants’ and ‘scale economies in transaction costs’ in isolation. The first model establishes that in the absence of double coincidence of wants, goods with low transaction costs are likely to be used as media of exchange. In this model, it is not necessary that the equilibrium gets established with a unique medium of exchange, rather there may be multiple monies. In the second model, the problem of double coincidence of wants is absent. Instead, the model focuses on scale economies. Here, it is assumed that the transaction costs of a commodity (or an instrument) decrease as its trading volume increases. That is, as individuals start using one commodity in their exchanges more and more, the commodity gets more marketable, which in turn leads other individuals to use this commodity in their exchange, and as this commodity gets more marketable its transactions costs decrease. The model shows that when there are increasing returns (i.e. in terms of decreasing transaction costs) to the increase in the trading volume of commodi- ties, a monetary equilibrium with a unique medium of exchange exists (i.e. H(1) confirmed).

Starr, as well as Kiyotaki and Wright, shows that the commodity money equi- librium exists, and that there is a state of ‘the model world’ where rational indi- viduals who try to maximise their expected utility would use media of exchange. Yet they do not show how exactly ‘the model world’ is transformed into such a state. To explain the emergence of a medium of exchange one needs to explicate the process through which a medium of exchange gets established. These models fail to do this. Later, we will return to this question when we examine the process models of ‘the origin of money’.9

2. The existence of fiat money equilibrium

In addition to the existence of commodity-money equilibrium, Kiyotaki and Wright analyse the existence of a fiat-money equilibrium (i.e. H(2)). Fiat money is an object (good 0) which does not have the intrinsic property of providing utility to the agents, but which nevertheless serves as a medium of exchange. Kiyotaki and Wright analyse whether such an object takes on value in their model world. They (1989: 942) find that there exist equilibria in which fiat money does not circulate. The intuition behind this result is the following: if no-one believes that the others will accept a valueless object (i.e. provides no utility), good 0, they will not exchange their goods with good 0. Kiyotaki and Wright show that fiat money can only exist if everyone believes that every other will accept it. Aiyagari and Wallace (1991), and Kiyotaki and Wright (1991, 1993) obtain similar results with more general models (see Appendix II). These models try to show that fiat-money equilibrium is another possible state of these model economies, but they fail to show that fiat money may emerge in these model economies without the existence of prior institutions or intervention.10 The reason for this is clear: these models fail to prove the existence of fiat-money equilibrium unless most of the agents (are assumed to) believe in the initial stage that the fiat good will be accepted by oth- ers.11 That is, they show that if everyone believes that everyone else will accept the fiat good in exchange then there is an equilibrium where the fiat good is used as a medium of exchange. Thus, if there is to be an equilibrium with fiat money, the common belief in its existence has to be established in the initial stage in some way. Yet these models do not explain how such a belief may be established or why agents would hold valueless objects and consider using them as media of exchange. In contrast to commodity money, it is not clear whether fiat money can get started if the faith is not imposed from outside (e.g. by a central authority). Thus, although these models assert that H(2) is confirmed, they fail to show this.

Of course, the fact that the proof of the existence of fiat money depends on an assumption of common belief is in line with our intuitions about the nature of money. Money exists only if everyone expects others to accept and use it in ex- change. This makes us understand (once again) that money is a stable institution; that is, if everyone believes that every other person will use it, no-one will have an incentive to stop using it.12 But the formal restatement of this intuition (i.e. about the nature of money) does not tell much about the origin of fiat money, or more precisely, about the way in which such a common belief gets established.

Alternatively, Williamson and Wright (1994) focus on an economy where there is uncertainty about the quality of commodities that are subject to exchange. The aim of the model is to analyse the function of money in reducing these uncer- tainties, which are caused by private information. The Williamson–Wright model abstracts from the problem of double coincidence of wants and assumes that all commodities of the same quality provide the same utility for all consumers in the model economy. It is also assumed that individuals may not be able to recog- nise the quality of a commodity in an exchange and thus their problem consists of deciding whether to exchange their commodities with another commodity of an unknown quality.13 They prove that under these conditions, when there is no private information (i.e. no uncertainty concerning the quality of commodities) only high-quality goods are produced and there is no need for money, but when there are uncertainties concerning the quality of goods, introducing a generally recognised fiat money to the economy improves welfare – as everyone can rec- ognise money and as there are no uncertainties concerning its quality. This model suggests that fiat money cannot be an unintended consequence of human action (H(2) is not supported) when there is uncertainty. Given their analysis, it is prob- able that while commodity money may emerge in a small economy, because of the uncertainties that may emerge from increased market size and traffic, at a point in history state intervention for refining the existent medium of exchange, or for replacing it by another one (e.g. fiat money) may become necessary (see Chapter 3). This explains the reason why Menger argues that unintended institutions may have to be refined at a point in history.

3. Concluding remarks

Remember that we have characterised Kiyotaki–Wright (1989) as focusing on certain aspects of Menger’s model world by way of leaving out other aspects of it. Other models that follow Kiyotaki and Wright (1989) are essentially doing similar things. They make similar further isolations to examine other aspects of Menger’s model world. As it may have been observed, these models also have a more spe- cific description of the trading environment and the way in which the trade takes place. Thus, they provide an understanding of what is possible (i.e. in terms of existence of monetary equilibrium) in such specific environments. Nevertheless, the explication of the process through which agents solve the problem of double coincidence of wants is needed for an explanation of the emergence of commodity money. More broadly, both in fundamental and speculative equilibria, individu- als expect others to use a certain good as a medium of exchange, but the above models do not tell much about how such a belief may be established. Thus, the criticism of end-state interpretation of the invisible hand is right on target (see Chapter 5).

Source: Aydinonat N. Emrah (2008), The Invisible Hand in Economics: How Economists Explain Unintended Social Consequences, Routledge; 1st edition.