Throughout this book, ever since the introduction of the five coordinating mechanisms in its first pages, we have seen growing convergences in its findings. For example, the standardization of work processes was seen in Chapter 1 to relate most closely to the view of the organization as a system of regulated flows. Then in Chapter 2, we saw these two linked up to the design parameter of behavior formalization in particular and the traditional kind of bureaucratic structure in general, where the operating work is highly specialized but unskilled. In the next chapter, we found that the operating units of such structures are large, and that they tend to be grouped by function, as do the units above them in the middle line. In Chapter 5, there emerged the conclusion that decentralization in these structures tends to be of the limited horizontal type, where power resides primarily at the strategic apex and secondarily in the technostructure that formalizes everyone else’s work. Then in the last chapter, we found that this combination of the design parameters is most likely to appear in larger and mature organizations, specifically in their second stage of develop- ment; in organizations that use mass production technical systems, reg- ulating but not automated; in organizations operating in simple, stable environments; and in those subject to external control. Other such con- vergences appeared in our findings. In effect, the elements of our study— the coordinating mechanisms, design parameters, and situational fac- tors—all seem to fall into natural clusters, or configurations.

It will be recalled that in our discussion of the effective structuring of organizations in the last chapter, two hypotheses were put forward. The congruence hypothesis, which postulates that effective organizations se- lect their design parameters to fit their situation, was the subject of that chapter. Now we take up the configuration hypothesis, which postulates that effective organizations achieve an internal consistency among their design parameters as well as compatibility with their situational factors—in effect, configuration. It is these configurations that are reflected in the convergences of this book.

How many configurations do we need to describe all organizations? The mathematician tells us that p elements, each of which can take on n forms, lead to pn possible combinations. With our various design param- eters, that number would grow rather large. Nevertheless, we could start building a large matrix, trying to fill in each of the boxes. But the world does not work that way. There is order in the world, but it is a far more profound one than that—a sense of union or harmony that grows out of the natural clustering of elements, whether they be stars, ants, or the characteristics of organizations.

The number “five” has appeared repeatedly in our discussion. First there were five basic coordinating mechanisms, then five basic parts of the organization, later five basic types of decentralization. Five is, of course, no ordinary digit. “It is the sign of union, the nuptial number according to the Pythagoreans; also the number of the center, of harmony and of equi- librium.” The Dictionnaire des Symboles goes on to tell us that five is the “symbol of man . . . likewise of the universe . . . the symbol of divine will that seeks only order and perfection.” To the ancient writers, five was the essence of the universal laws, there being “five colors, five flavors, five tones, five metals, five viscera, five planets, five orients, five regions of space, of course five senses,” not to mention “the five colors of the rain- bow.” Our modest contribution to this impressive list is five configurations of structure and situation. These have appeared repeatedly in our discus- sion; they are the ones described most frequently in the literature.1

In fact, the recurrence of the number “five” in our discussion seems not to be coincidental, for it turns out that there is a one-to-one correspon- dence among all our fives. In each configuration, a different one of—the coordinating mechanisms is dominant, a different part of the organization plays the most important role, and a different type of decentralization is used.2 This correspondence is summarized in the following table:

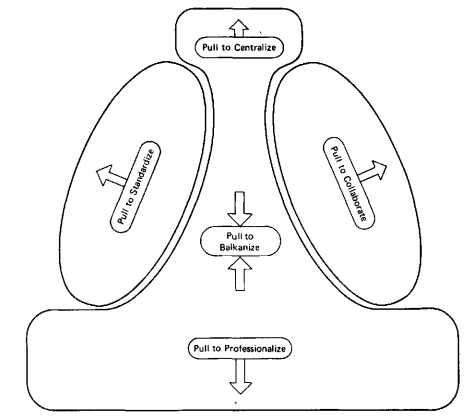

We can explain this correspondence by considering the organization as being pulled in five different directions, each by one of its parts. (These five pulls are shown in Figure7-1.) Most organizations experience all five of these pulls; however, to the extent that conditions favor one over the others, the organization is drawn to structure itself as one of the configurations.

- Thus, the strategic apex exerts a pull for centralization, by which it can retain control over decision This it achieves when direct supervision is relied upon for coordination. To the extent that conditions favor this pull, the configuration called Simple Structure emerges.

- The technostructure exerts its pull for standardization—notably for that of work processes, the tightest form—because the design of the stan- dards is its raison d’etre. This amounts to a pull for limited horizontal To the extent that conditions favor this pull, the organi- zation structures itself as a Machine Bureaucracy.

- In contrast, the members of the operating core seek to minimize the influence of the administrators—managers as well as analysts—over their That is, they promote horizontal and vertical decentralization. When they succeed, they work relatively autonomously, achieving what- ever coordination is necessary through the standardization of skills. Thus, the operators exert a pull for professionalism—that is, for a reliance on outside training that enhances their skills. To the extent that condi-tions favor this pull, the organization structures itself as a Professional Bureaucracy.

Figure 7-1. Five pulls on the organization

- The managers of the middle line also seek autonomy but must achieve it in a very different way—by drawing power down from the strategic apex and, if necessary, up from the operating core, to concentrate it in their own In effect, they favor limited vertical decentraliza- tion. As a result, they exert a pull to Balkanize the structure, to split it into market-based units that can control their own decisions, coordination being restricted to the standardization of their outputs. To the extent that conditions favor this pull, the Divisionalized Form results.

- Finally, the support staff gains the most influence in the organiza- tion not when its members are autonomous but when their collaboration is called for in decision making, owing to their expertise. This happens when the organization is structured into work constellations to which power is decentralized selectively and that are free to coordinate within and between themselves by mutual adjustment. To the extent that condi- tions favor this pull to collaborate, the organization adopts the Adhocracy configuration. (See Chapter 12.)

Consider, for example, the case of a film company. The presence of a strong director will favor the pull to centralize and encourage the use of the Simple Structure. Should there be a number of strong directors, each pull- ing for his or her own autonomy, the structure will probably be Balkanized into the Divisionalized Form. Should the company instead employ highly skilled actors and cameramen, producing complex but standard industrial films, it will have a strong incentive to decentralize further and use the Professional Bureaucracy structure. In contrast, should the company em- ploy relatively unskilled personnel, perhaps to mass-produce spaghetti westerns, it will experience a strong pull to standardize and to structure itself as a Machine Bureaucracy. But if, instead, it wishes to innovate, resulting in the strongest pull to collaborate the efforts of director, design- er, actor, and cameraman, it would have a strong incentive to use the Adhocracy configuration.

These five configurations are the subject of the remaining chapters of the book. The description of each in the next five chapters serves two purposes. First, it enables us to propbse a fundamental way to categorize organizations—and the correspondences that we have seen give us some confidence in asserting that fundamentality. And second, by allowing us to draw together the material of the first six chapters, the descriptions serve as an excellent way to summarize and, more important, to synthesize the findings of this book.

In describing these configurations, we drop the assumption that the situational factors are the independent variables, those that dictate the choice of the design parameters. Instead, we shall take a “systems” ap- proach now, treating our configurations of the contingency and structural parameters as “gestalts,” clusters of tightly interdependent relationships. There is no dependent or independent variable in a system; everything depends on everything else. Large size may bureaucratize a structure, but bureaucracies also seek to grow large; dynamic environments may require organic structures, but organizations with organic structures also seek out dynamic environments, where they feel more comfortable. Organiza- tions—at least effective ones—appear to change whatever parameters they can—situational as well as structural—to maintain the coherence of their gestalts.

Each of the five chapters that follows describes one of the configura- tions, drawing its material from every chapter of this book. Each chapter begins with a description of the basic structure of the configuration: how it uses the coordinating mechanisms and the design parameters, as well how it functions—how authority, material, information, and decision processes flow through its five parts. This is followed by a discussion of the condi- tions of the configuration—the factors of age, size, technical system, en- vironment, and power typically associated with it. (All these conclusions are summarized in Table 12-1.) Here, also, we seek to identify well-known examples of each configuration, and to note some common hybrids it forms with other configurations. Finally, each chapter closes with a discus- sion of some of the more important social issues associated with the config- uration. It is here that I take the liberty usually accorded an author of explicitly injecting my own opinions into the concluding section of his work.

One last point before we begin. Parts of this section have an air of conclusiveness about them, as if the five configurations are perfectly dis- tinct and encompass all of organizational reality. That is not true, as we shall see in a sixth and concluding chapter. Until then, the reader would do well to proceed under the assumption that every sentence in this section is an overstatement (including this one!). There are times when we need to caricature, or stereotype, reality in order to sharpen differences and so to better understand it. Thus, the case for each configuration is overstated to make it clearer, not to suggest that every organization—indeed any organi- zation—exactly fits a single configuration. Each configuration is a pure type (what Weber called an “ideal” type), a theoretically consistent combination of the situational and design parameters. Together the five may be thought of as bounding a pentagon within which real organizations may be found. In fact, our brief concluding chapter presents such a pentagon, showing within its boundaries the hybrids of the configurations and the transitions between them. But we can comprehend the inside of a space only by identifying its boundaries. So let us proceed with our discussion of the configurations.

Source: Mintzberg Henry (1992), Structure in Fives: Designing Effective Organizations, Pearson; 1st edition.