1. Basic Departments in Six Organizations

Each of the six plastics organizations studied was a major product segment of a large, diversified chemical company. While there were some differences in their products, they all competed in the manufacture of basic plastics materials for sale to industrial customers. Each organization was a self-contained entity, carrying out a complete cycle of designing, marketing, and manufacturing. In general, the only constraints imposed by the corporate headquarters were at the broadest policy level, where decisions might affect more than one product segment of the corporation.

Each of these organizations had four basic functional departments—sales, production, applied research, and funda- mental research. The functions of the sales and production departments were already evident from what we have said about the nature of the environment. The two research units dealt with different phases of the scientific segment of the environment. As the title implies, fundamental research departments were generally supposed to relate to the less certain aspects of relevant scientific knowledge. Although all the applied research laboratories dealt with the more certain scientific problems, their assigned missions varied as we shall see later.

In examining these four basic departments, we will first summarize how earlier behavioral science researchers had suggested that they should be differentiated in order to deal effectively with the differing degrees of certainty in their respective parts of the environment. This will take the form of a description of particular required internal characteristics of each department. Second, we will report our empirical findings on the actual internal characteristics. This will tell us to what extent these departments were consistently different from one another in each predicted dimension.

2. Formality of Structure, Predicted and Actual

The first dimension we examined was formality of structure. Did the basic departments show differences in formal structure that could be related to differences in the certainty of their part of the environment? We expected, from earlier behavioral studies, that the research units, dealing with highly uncertain tasks, would be less formally structured than the production units. Organizational practices and procedures would, we thought, be less controlling and constraining than in production departments, because the task would require a setting where scientists and engineers could openly and freely explore scientific problems with one another. On the other hand, we expected that production managers, to do their jobs effectively, would require more established routines and tighter controls. The task of the sales departments, which fell between the other two in certainty, would, we assumed, require a departmental structure between the extremes of the other units.

We collected our data on formality of structure by examining organizational manuals and charts and by interviewing each department manager about the practices in his unit. These data indicate that the differences among departments were in a direction that could reasonably be related to envi- ronmental certainty. The production units have the most formalized structure in four of the six organizations. In the other two, the production unit has either the next to highest formality of structure or was tied for highest. Compared with the other departments in each organization, the production units had more levels in the managerial hierarchy and a higher ratio of supervisors to subordinates, as well as more frequent and more specific reviews of both the department’s and individual managers’ performances. Precise data for judging performance were quickly available and readily used. Similarly, since the manufacturing units’ activities could largely be programmed in advance, these units relied more on formal rules and procedures than did the sales or research units.

At the other end of the spectrum were the fundamental re- search units. In four of the organizations this laboratory had the least formal structure, and in the other two it was tied for the least. Specifically, more subordinates reported to each supervisor, and there were fewer levels in the managerial hierarchy. Performance reviews were general and infrequent, and there was little reliance on written rules or procedures.

The structures of the applied research laboratories and the sales departments fell between the extremes represented by production and fundamental research. In general, the sales units were more structured than the applied research laboratories. This, too, is consistent with relative environmental certainty. These data, then, strongly indicate that there were differences in the structural features of the various departments in each organization, and that these differences were related to the nature of that phase of the environment with which each unit was dealing.

3. Interpersonal Orientation, Predicted and Actual

The second dimension along which we measured differences among departments was the kinds of interpersonal relationships among department members. Prior research had suggested that the members of different departments would find it necessary, if they were to be effective, to develop different interpersonal orientations related to the nature of their task. Specifically earlier work had suggested that members of units engaged in either highly certain or highly uncertain tasks would develop task-oriented interpersonal styles. Members of units with moderately uncertain tasks would develop relationship-oriented styles.3 Thus, production engineers, plant managers, and other manufacturing personnel whose tasks were very certain would generally, we predicted, prefer interactions aimed primarily at getting the job done and would not be particularly concerned about maintaining social relationships. Sales and marketing managers, who were dealing with a moderately uncertain task and who were also accustomed to being concerned with customer relations, would be expected to care more about fostering positive social relationships among their co-workers. Research scientists and engineers were expected to fall between the production and sales extremes, with the fundamental scientists preferring contacts which emphasized task accomplishment. The high uncertainty of their jobs, which were often carried out individually, would lead them, we predicted, to be less concerned with social relationships than applied research personnel who had more certain tasks.

To measure interpersonal orientations we used a standard paper-and-pencil instrument, which indicates a person s preference for relationship-oriented or task-oriented interactions. The data collected generally supported our predictions. In two of the six organizations the sales departments were the most relationship- oriented, and in the other four they were the second in this respect. Production personnel indicated a preference for task-oriented relationships. They were the most task-oriented in four of the organizations and were tied for second in a fifth. (Production personnel in the sixth organization deviated from this pattern, for reasons to be explained shortly.) Since the production procedures and controls and the processing technology provided the necessary coordination within the department, production personnel generally did not see positive social relationships as essential. If these managers found it difficult to work with a particular colleague, their attitude was to get on with the job without special regard for maintaining positive relationships. Both fundamental and applied research personnel fell between the extremes of production and sales in their interpersonal orientation. The applied people having a moderately uncertain task leaned toward the relationship orientation of sales and the fundamental researchers tended more toward the task ori- entation of production. Thus these differences in orientation were also generally consistent with our predictions drawn from earlier research.

4. Time Orientations, Predicted and Actual

We expected that members of these four basic departments, because of environmental differences, would also develop dif- ferent orientations toward time. Sales and production personnel, dealing with problems that often provide rapid feedback about results, would, we assumed, have their attentions focused on short-term matters. Research scientists and engineers would, we thought, have longer-range concerns, because tangible results of their efforts could be judged only when they had solved the scientific and technical problems leading ultimately to a new product or a new process. People working in these research settings would need to be comfortable in delaying the gratification they received from feedback about the results of their work. As with any of these attributes, in de-scribing the required time orientations we are obviously only describing our predictions about a general tendency in the indicated direction. Certain managers within the manufacturing unit may be required to be concerned about longer- term operations, and certain research personnel may be working at solving a particular customer problem where success would be evident within a few weeks.

The time orientation was measured by asking managers, in the questionnaire, how much of their time was devoted to activities that contributed to company profits in different future time periods—one month or less; one to three months; three months to one year; and one year or longer. Here again, we found support for our prediction about the relationship between the nature of each part of the environment and the orientation of departmental personnel. The primary time orientation of members of each department was related to the time span of definitive feedback. The members of both the production and sales departments reported that most of their work dealt with matters that would affect profits relatively soon, often less than one month in the future. This was consistent with the rapid feedback available from both the market and the techno-economic portions of the environment. In contrast, administrators and scientists in the fundamental laboratories were oriented primarily toward much longer time horizons, often several years in the future. Again this was consistent with environmental demands, since the final evidence of success or failure in their activities was available only when a project was ended, which usually required a year or longer. While the members of the applied research laboratories in most of the organizations also focused on longer-term objectives, there were some exceptions that gave the total group a medium-term to long-term orientation. These exceptions seemed to grow out of differences in the assigned activities of these units, which we will discuss shortly.

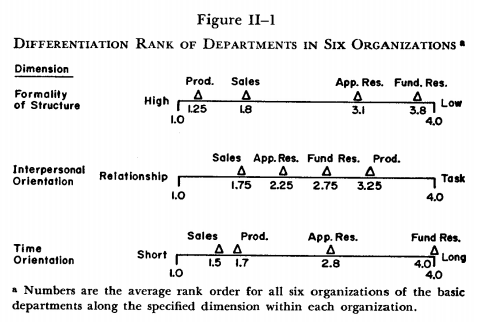

Figure II—1 summarizes the data on the three dimensions we have examined so far—formality of structure and interpersonal and time orientations—for the basic departments in all six organizations. It suggests quite clearly that across all organizations there were differences among departments that were consistent with our predictions. It should be emphasized, as indicated above, that structure and time orientation ap-pear to vary in almost a linear relationship to the certainty of the task, while interpersonal orientation has more of a curvilinear relationship to certainty. When the task is either very certain or very uncertain members prefer task-oriented interactions, but when the task is moderately certain they rely more on relationship-oriented interactions.

5. Goal Orientation, Predicted and Actual

The fourth, and probably most obvious, way in which we expected these departments to differ is in the orientation of their members toward goals and objectives. This attribute is not related to the certainty of the parts of the environment, but simply to the fact that each of the functional units had been assigned the job of dealing with a particular aspect of the total environment. If these managers were to be effective in doing their specialized tasks, they must focus their attention clearly on objectives and goals directly related to them. Sales managers must be concerned with accomplishing market objectives. Manufacturing managers must pay attention to such techno-economic goals as processing costs, raw materials costs, and the quality of the finished product. Research personnel must be primarily concerned with both the development of new scientific knowledge and its successful application to products and processes. In each case we were interested to see whether the members of each unit had their attention tightly focused on the specific goals of their department, or whether their concerns were more diffused. Data to measure this orientation were collected on the questionnaire by asking managers to indicate their concern with nine different decisionmaking criteria—three each dealing with the market, techno- economic factors, and science—e.g., the probable response of competitors to the decision (the market) ; the effect of the decision on contributions to scientific knowledge (science); and the plant facilities required by the decision (techno- economic) .

Our prediction in this area also turned out to be largely true. Sales personnel in all six organizations indicated a primary concern with customer problems, competitive activities, and other events in the marketplace. Manufacturing personnel were all primarily interested in problems of cost reduction, process efficiency, and similar matters.

In the research laboratories, however, we did not find so strong an orientation as we had expected toward scientific objectives. In three of the organizations fundamental scientists did indicate a primary concern with the development of new knowledge, but in the other three they were more concerned with such techno-economic factors as technological improvements for cost reduction and quality control. A similar orientation was reported in all but one of the applied research units. Although we had anticipated that these personnel would be strongly attuned to scientific goals, in retrospect this result is not too surprising because much of the activity in these laboratories, particularly the applied ones, was devoted to process improvements and modifications. In any case, in those research units where scientists and engineers indicated a primary orientation toward techno- economic goals they also indicated a strong secondary concern with scientific factors.

At this point it is important to review briefly the arguments and evidence that we have so far presented. Based on our prior evidence about the environment of the plastics industry, we expected to find variations in the amount of uncertainty present in the different environmental sectors. Both the interview data from key executives and our measurement of uncertainty factors supported this prediction. We further predicted that the basic departments in each organization would tend to be different from one another along four important dimensions. We have presented data that clearly show that this was, in fact, true. The departments were differentiated in ways that were predicted, relative to environmental attributes. While the existence of these differences will probably come as no surprise to most businessmen, it not only confirms general impressions but, more importantly, provides an explanation of why there are differences among basic departments. We must emphasize, however, that these findings indicate only a general tendency toward the predicted pattern of differentiation, and that it is still problematic how precisely the pattern in any one organization will fit its environment. The key question is: Were the organizations that have achieved the closest fit between departmental differentiation and the attributes of their environment also the high per-formers in terms of economic results? Having prepared the way to address this question, we will start by examining data about the performance of these six organizations.

Source: Lawrence Paul R., Lorsch Jay W. (1967), Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration, Harvard Business School.