The plastics industry could be defined as extending from the basic bulk chemicals from which the plastics compounds are developed to the final product in the multitudinous forms in which it reaches the hands of the consumer. For the sake of better comparability among organizations, we limited our study to firms that produced and sold plastics materials in the form of powder, pellets, and sheets. Their products went to industrial customers of all sizes, from the large automobile, appliance, furniture, paint, textile, and paper companies, to the smaller firms making toys, containers, and household items. The organizations studied emphasized specialty plastics tailored to specific uses rather than standardized commodity plastics. They all built their product- development work on the science of polymer chemistry. Production was continuous, with relatively few workers needed to monitor the automatic and semiautomatic processing equipment.

Before we could begin our examination, we had to learn what demands this environment placed on organizations within it. To answer this question we interviewed the senior executives in each of the six organizations studied and also asked them to complete a questionnaire that measured certain attributes of their industrial environment as they saw them.

These executives indicated in interviews that the dominant competitive issue confronting them was the development of new and revised products and processes. The life cycle of products was dwindling. Without new products any single firm was doomed to decline. And since all firms were steadily introducing new and revised products and processes, the future course of events was highly uncertain and difficult to predict.

According to these executives, the most hazardous aspect of the industrial environment revolved around the relevant scientific knowledge. It was difficult at any point in time to say just what all the relevant knowledge on a given topic was and just how certain it was. Cause and effect relationships were not well understood. Further contributing to this lack of certainty was the long time required to get feedback about whether a particular scientific investigation had been fruitful. One executive put it this way:

We very often know the performance characteristics re-quired by a customer or for a new application, but as far as research is concerned, you might as well be asking for the perfect plastic. We have to be concerned with technical feasibility right from the start, and then you don’t know as you are involved in a lengthy testing and development process.

The general manager of another organization further emphasized the uncertainties of scientific knowledge:

The development of plastics materials is more of an art than a science. We often don’t fully understand what is needed to meet customer requirements, and if we do, we don’t know how we can process it. However, we have developed the art to a high enough degree so we can hit the target area, even if we can’t hit the target in every case.

The research director in another organization stressed the lack of understanding of cause and effect relationships:

One problem in the development of new applications is the identification of a need. Once we have identified this, we can easily establish the required product specifications. Of course, achieving them is another thing. The problem here is that our knowledge is not nailed down as precisely as it is, say, in chemicals. Sure we are able to do a lot of things by trial and error, but this is solving problems without knowing the reason why.

As these comments suggest, all the top managers interviewed felt knowledge about the market was more certain than scientific knowledge. Customer needs and other required information could be specified at any particular time. Causal relations were better understood. For example, the result of a price change could be predicted with some accuracy. Furthermore, definite feedback about the results of some action in the market was available quickly, often within a month. Yet there were a number of uncertainties, many stemming from the great variety of customer needs. There were also problems in specifying all the variables that must be taken into account. As one executive said:

The market we sell to is broad and diverse. For example, in the toy business if the product comes out in the right color at the right price, anybody will buy it, and anybody can make it. In contrast, for wire and cable customers, the right technology, service, and delivery are critical, and price is at the end of the line. Usually some minor technical property sells your product in that business. It is very rare that you get exact duplication from anybody.

Another manager made the same point:

Because our customers typically use the products we sell in a chemical reaction, we have a relatively high level of control over the suitability of our product to the customer. In other words, how the customer uses the product affects its utility to him. Consequently, we have a hundred markets, each different in requirements because of the customers’ processing needs.

While scientific knowledge was highly uncertain, and the market moderately uncertain, technical and economic fac-tors, according to these executives, were more predictable. Once the product specifications had been developed, the technical and economic knowledge needed to carry out the manufacturing process were highly certain. At this stage the desired product characteristics were well defined from both a technical and a cost standpoint, and production personnel had particular targets to shoot at. Highly reliable information could be obtained about how well the process was operating. The devices necessary to monitor the major production variables—e.g., pressure, temperature, and chemical composition—were often built right into the production process. Causal relationships among these variables were also relatively well defined. Finally, the time required to get clear information about the consequences of actions in this area was short—at most only a matter of hours or days. As one executive commented:

In production, life is really plain, as it is geared to running the kind of plant and equipment which they currently have and where most of the decisions are built in.

While what we call “environment” is fairly self-evident as applied to research and marketing, the use of this term in relation to production requires some explanation. Contrary to conventional usage, we have chosen to conceive of the physical machinery, the nonhuman aspect of production, as part of its environment. Production executives must draw information from this equipment’s performance and analyze it in terms of costs, yields, and quality, just as they must also draw information from outside the physical boundaries of the firm about newly available equipment and alternative processes. It is this information and knowledge from all these sources that we are interested in characterizing as certain or uncertain. Readers who find this awkward may prefer to think in terms of “the production task” rather than of the “techno-economic environment.”

In short, what the top executives in these organizations told us about the environment of the plastics industry was that different phases of it vary in degree of certainty. One manager summarizes their conclusions very well:

The requirements in this industry are that you must have good and continuing technology, sound economics in your production, and you must market your product at the lowest costs. I’d say these are all equal. But first among equals, and the most critical, are the research and marketing areas. I would say that they are the most critical and the most diffi- cult because there are so many variables involved. You know what you are doing in production. You have the facts there.

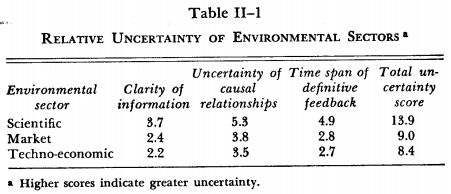

The data collected in our questionnaires generally confirm the conclusions we reached through the interviews (Table II—1. The clarity of information, the uncertainty of cause and effect relationships, and the time span of definitive feedback scores have been combined to get a total uncertainty score. While the differences in the uncertainty scores for different parts of the environment are not highly significant, the order is clearly in the expected direction, indicating, as do the interview data, that scientific knowledge is least certain; market knowledge, next; and techno-economic knowledge, most certain.

One slight disparity between the data gathered in ques- tionnaires and the impressions we gleaned from our interviews concern the relative uncertainty of the market and techno- economic information. In interviews, the managers indicated that the market was considerably the less certain of the two. While their responses to questionnaires tended in this same direction, the differences were not so great as the interviews led us to expect. The reason seems to lie in the phrasing of the questionnaire, which focused more on the task of the sales unit itself and less on the nature of the market. Since much of the market uncertainty was handled by groups other than the line sales department (e.g., development departments, product integrators), the task of the sales group was seen as more certain than the oral descriptions of the market suggested. This seemed to be particularly true with respect to the clarity of information about the market. On this point, therefore, we have relied more on the evidence gathered in interviews than on responses to the questionnaire.

From all these data we concluded that the differences in uncertainty among these three aspects of the environment were such that the primary task of each major functional department was essentially different. As we suggested in Chapter I, this would mean that different orientations and organizational practices would tend to develop within each of the basic departments. We will review below our specific hypotheses about these departmental differences and compare them with our empirical findings.

Source: Lawrence Paul R., Lorsch Jay W. (1967), Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration, Harvard Business School.